Exploring US music’s missing history

American music’s history’s big black hole.

When researching my blues and American music history book, America’s Gift, I became slowly aware of how a huge slice of America’s musical past had virtually disappeared into what South Carolina’s Cradle of Jazz Project has described as a black hole.

Come to think of it, it was the very existence of this black hole that made me to start researching the history of blues, and the music preceding it, in the first place. How blues had evolved was something I’d wondered about since the age of 14 or 15, when I first started listening to Albert King, Memphis Slim and all the other great blues performers whose records I bought in the 1960s. This was so long ago, Muddy Waters had yet to be rediscovered. That he was rediscovered, for those unaware, is mainly down to the Rolling Stones.

For much of the twentieth century, I found hardly anything to enlighten me about America’s musical goings-on before blues was named, in 1912. The nineteenth century seemed a no-go area, possibly due to the history of the blues including areas, understandably, highly offensive to the African-American community. Whatever the reason, a large slice of U.S. pop music history appears ignored, buried and forgotten. I hope this is for reasons other than political correctness. Now, I’m all for PC-ness, but I think it takes a step too far when it buries the facts, which are these:

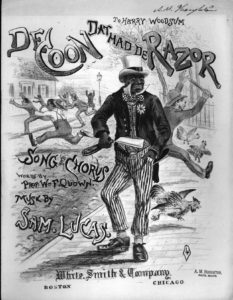

During the 1880s and 1890s, the USA and English-speaking world developed a huge appetite for a nasty musical genre which went under the banner of coon songs. This genre, immediately preceded ragtime, which directly led to the first published and recorded blues. For a while there, rags were called blues and blues were called rags. Nobody could pick the difference. Their predecessor, the coon song, had been at its most popular during the 1880s. That over 600 such songs were published in the following decade, the 1890s, when the genre was tailing off, proves how widespread coon songs were in the 1880s. As I say in America’s Gift, “Their lyrics spewed out an undercurrent of extreme viciousness which seemed to unleash all the hate and resentment held by certain sections of American society after the South’s Civil War defeat”.

Political correctness certainly had no place in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Blacks, as well as whites, wrote and performed coon songs, caricaturing black people. Jews and gentiles wrote and performed ‘Jew face’ songs, caricaturing Jewish people. The African-American entertainer Sam Lucas even had a popular number called ‘Ole Nicker Demus De Ruler Ob De Jews’.

The speech patterns and cultural idiosyncrasies of all sorts of nationalities, including Chinese, Irish, Italians, Germans, Poles, Scandinavians and the white American and English yokel, were lampooned in the USA in what were known as dialect comedies, on vaudeville stages across the United States, by performers from all sorts of backgrounds.

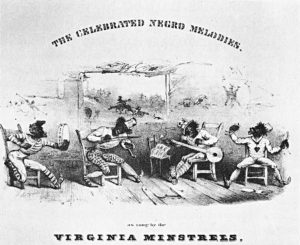

Before coon songs, of course, there was the minstrel genre, the form of song and dance that ran from the 1840s to, unbelievably (and shamefully), the 1970s. Again, I understand just how offensive minstrelsy is to today’s black communities. At the same time, it must be recognised that many black entertainers had no choice but to write and/or perform minstrel and coon songs, if they wanted to earn a living. Such performers even included blues icons like W.C. Handy, Ma Rainey and Charley Patton.

For a more on coon and minstrel songs, can I suggest my book, America’s Gift, which lays out, in far more detail than here, the important contributions those controversial music genres made to American popular music and blues in particular. To ignore them, I feel, is like pretending blues’ other ancestor, slavery, also didn’t exist. Just because you don’t agree with something doesn’t mean you whitewash it from history. That’s my view anyway.

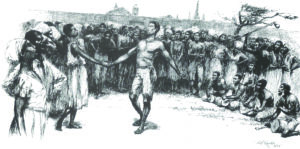

As for singing the blues’ forerunners while literally working like slaves for their owners in the South’s proverbial cotton fields, it’s significant to note that there are no references to narrative work songs sung by African-American slaves before the American Civil War. This means the blues song, as we know it today, had its origins after the Civil War.

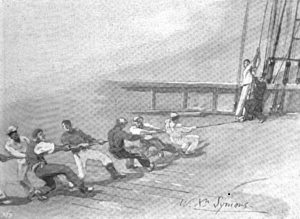

So, from where do you think America’s slaves got the idea to sing while they worked? I found a clue buried away in an 1882 edition of New York’s Harper’s New Monthly magazine. This was in an article written by the prominent nineteenth century American journalist and diplomatic. He’d noticed musical similarities between earlier sailor’s sea shanties, African-American work songs and some minstrel songs, the pop songs in vogue at the time he wrote his article. He also wrote about certain African tribesmen who worked on American merchant ships from 1790. The songs of these Africans, it seems, merged with the songs of the sailors and the sea-shanty era began. Contrary to what many believe, sea shanties were a uniquely American form of song, not even named as sea shanties until the twentieth century. The term may easily have come from the title used by the (usually) black shanty-man or chanty-man, who was the foreman who led the singing as his gang worked on U.S. ships, docks or Mississippi river boats. Shanty men often improvised their chants in true African-American style, lengthening them where necessary, along the same lines as floating verses would later be incorporated into the blues. His twentieth century descendant was truly the blues singer.

You’ll notice I said the shanty man was probably black. This is because, again contrary to popular belief, some workers on America’s Southern docks were actually white. There traditionally included English sailors escaping the harsh Northern winters back home, who would labour alongside free blacks plus slaves hired out to the docks by greedy plantation owners.

You can read more about how minstrel and post-Civil War African-American work songs were influenced by the sea shanties of the 1840s in America’s Gift.

Just to show how poorly documented American music history has now become, the actual message put out by the Cradle of Jazz Project was this:

“From the end of the dances at Congo Square to the beginning of jazz, there is a black hole of less than 50 years when the old West African music slowly turned into the new music of America.”

The Project are quite right when they say West African music was played in New Orleans’ Congo Square. This was under French and Spanish rule, before the USA took over New Orleans in 1803. American authorities had much harsher attitudes to music and Congo Square gradually lost its impetus.

Black celebrations at Congo Square had totally died out by the Civil War, so there’s no way American influences on African music could have sown the seeds of blues.

The first appearances of the words blues and jass were found in newspapers in 1910 with the first blues recording taking place in 1914, and the first jass recording in 1917. This was also the year jass became jazz.

Now, if you fancy seeing some fantastic aerial footage of America, while putting up with some points about America’s missing musical history backed by Derek and the Dominoes-style12-bar blues, get stuck into the video below

I was interested reading your site – My age group mainly have rarely exhibited much antagonism towards other races, indeed been aware some words are derogatory. Or knew the difference between coloured or black!! I, at 72yrs inherited a copy of Famous American Coon, Lullaby and Plantation Songs, Book 2. This book contains ten songs/music scores: My Lady Lu; Mammy’s Little Kinky-Headed Honey + eight more. Origin: Herman Darewski Music Publishing Co. Incorporating Charles Sheard & Co. London WC2 Price: One Shilling!

Regards

Geoff & Joy Warr, London

Thanks for your feedback, guys. As mentioned in my book, America’s Gift, the term ‘coon’ started life as a positive African-American description for black people respected in their communities. Only in the 1880s did it start to become offensive, due to the popularity of coon songs, written by both black and white songwriters. Your inherited song book sounds fascinating.