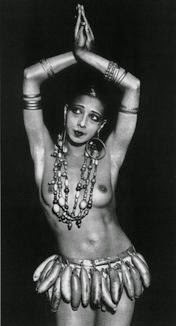

Eartha Kitt sings the most influential blues of all time.

If I told you W.C. Handy’s classic “St. Louis Blues” was the most influential blues song ever recorded, would you believe me? Possibly not.

You may well be thinking of an important blues by Big Bill Broonzy, Willie Dixon, or even Cream, a song that brought blues to the masses. However, my case is pretty watertight, I’m convinced. Indeed, I’ve just made a short film on the 101-year heritage of St. Louis Blues which, as I re-examined the song, reinforced my conviction.

Even before you read (or hear if you watch the film) what I’m going to tell you, let me remind you that St. Louis Blues has long been the song many traditionalist rate as the greatest blues standard of all time. That’s not Eartha below, of course, but she’s certainly in the film. Check it now – if you can spare five minutes.

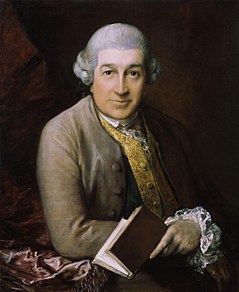

Recorded for the first time in December 1915, St. Louis Blues was written and published a year earlier by that pioneering African-American bandleader, W.C. Handy.

Handy wasn’t first to record the song, not by a long chalk. St. Louis Blues was first recorded in New York, apparently in two takes, by Columbia Records all-white house band, led by a descendant of two U.S. Presidents, would you believe, Charles Adams Prince (descended from John Adams and John Quincy Adams). You might find it incredulous to find that all American blues recordings up to 1920 were made by white singers and orchestras. It’s ludicrous but true. (W.C. Handy, incidentally, also composed the very first blues song recorded, The Memphis Blues, which had three different versions cut in 1914. See 11 Dec 2013 archive.)

But back to St. Louis Blues. Released in Britain, before anywhere else in 1916, Prince’s recording of St. Louis Blues is generally regarded as the track that introduced blues to the world – but not from America. In an interesting aside, 1916 was also the year that Handy offered the delta blues pioneer, Charlie Patton, then aged 25, a position in his band as the guitarist. Charlie turned it down, preferring to stay solo. 1916, to add some perspective, was also the half-way stage of World War 1 and the year of the infamous Battle of the Somme in France, which saw over a million men killed or wounded.

When I was writing about St. Louise Blues in my book, America’s Gift, I felt on the verge of a bit of a blues scoop, because it’s long been considered that the first black artist ever recorded singing or playing the blues was Mamie Smith. This was in August 1920 when Mamie cut Crazy Blues while standing in for Sophie Tucker. But staring me in the face was the fact that the first version of St. Louis Blues recorded with vocals was cut in London in September 1917. Significantly, it was by the Ciro’s Club Coon Orchestra to give them their obnoxious full moniker, a group of black American musicians working in England. Forgive me mentioning the band’s tasteless name in full, but I want to put the Ciro band’s name into historical perspective. Coon songs were, by 1917, out of fashion in America, due to white society at last beginning to realise how insulting a word that was. As a result, coon shouters like Sophie Tucker were, in the USA, becoming known as blues shouters, instead. Britain, obviously, was a bit behind the times when it came to the evolution of musical genres.

By my reckoning, this 1917 UK recording of St. Louis Blues makes Ciro’s Orchestra the first black artists known to put blues on record. Not only that, it was a blues with vocals too. The Ciro’s band recorded three years before Mamie Smith, who is generally considered the first black artist to record a blues song, which she did with ‘Crazy Blues’ in 1920. Even though it’s now established Mamie wasn’t the first, she was still the one who opened the door for all those African-American blues divas who would follow and, during the 1920s, formulate the blues singing style now taken for granted. Take a listen to this historic recording below.

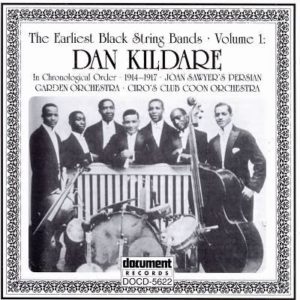

So, who was Ciro’s Club Orchestra and what were they doing in England during the First World War? First up, Ciro’s was a swanky nightclub located in Orange Street, just off Charing Cross Road in London. Decorated in Louis XIV style, with a sliding roof and a dance floor on springs, it was the place in London for bright young things and high society to be seen. The Ciro’s Club’s house band was led by a Jamaican pianist called Dan Kildare, born in Kingston in 1879.

By his early twenties, Dan was doing well for himself in New York until musician union issues and racial politics ‘encouraged’ him to sail to Liverpool, England, in 1915. Kildare took with him a number of African-American musicians from New York’s Clef Club (a social club and booking agency) and they secured themselves a year’s contract at the Ciro’s Club, not far from the intersection of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road in London’s West End district. Under the appalling name of Ciro’s Club Coon Orchestra, Dan Kildare’s band cut a series of records in August and October 1916 for the Columbia label in the UK including several novelties, a handful of Hawaiian numbers and the first version of St. Louis Blues ever recorded with vocals. (Some 55 years later, I’d find myself working for the same organisation – CBS Records, then in Theobald’s Road, London.)

As the gossip columnist for the UK’s upmarket Tatler magazine of September 1916 wrote in that patronisingly posh style of the English upper class 100 years ago:

“I don’t know what one would do to keep one’s spirits (up during WW1) if it weren’t for the theatres and restaurants, and the little dances, with Ciro’s band to bang away till breakfast time. The coon music, by the way, isn’t getting depressed at all – in fact, it’s madder than ever.”

Dan Kildare’s group of African-American musicians also played many high society gigs during their time in London, including a garden party at Grosvenor House attended by Winston Churchill and British Prime Minister, Lord Asquith. Kildare’s orchestra would have been known as a string band in those days.

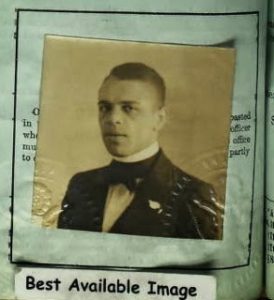

Featured on their historic St. Louis Blues recording were Dan’s brother Walter Kildare who probably provided the  vocals; Vance Lowry, banjo; Ferdinand Allen, banjoline (cross between a banjo and mandolin) Sumner “King” Edwards, bass, and Hugh Pollard, drums. Who’s who on the Document Records cover to our right, I can’t say.

vocals; Vance Lowry, banjo; Ferdinand Allen, banjoline (cross between a banjo and mandolin) Sumner “King” Edwards, bass, and Hugh Pollard, drums. Who’s who on the Document Records cover to our right, I can’t say.

When Ciro’s Club was shut down for selling unlicensed booze in 1917, most of the band, including Dan’s West Indian brother, headed for France to join the American Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. Many African-American troops were then attached to the French army, which became the catalyst that started the French jazz craze following WW1.

From then on, Dan Kildare’s life hit that drugs and alcohol-fuelled downward spiral so commonly familiar to rock, jazz and blues musicians, from Buddy Bolden being banged up for insanity in 1907, onwards.

The Jamaican pianist stayed in London, performing in Dan and Harvey’s jazz band with the drummer, Harvey White, and publishing original compositions. Apparently, he was earning good money and doing well.

Dan Kildare, by now, had married a lady who owned a local pub, a Mrs Fink.

On 21 June 1920, Dan Kildare, aged 41, walked into Mrs Fink’s pub, shot her dead, shot and killed Mrs Fink’s sister, then killed himself with a bullet in the head. His legacy is now almost forgotten and it would be nice if Dan Kildare started getting the recognition he deserves in the centenary year of the first ever recorded blues release.

And if you know of any black musician who may have recorded a blues track before Dan Kildare and his Ciro’s Orchestra in 1917, please let me know. Because it’s odds-on your musician will turn out to be the world’s first recorded blues artist.