The world’s first anti-rock review?

How George Bernard Shaw wrote the world’s first anti-rock music review.

Let’s go all literary today and talk about the Nobel Prize-winning author and playwright, George Barnard Shaw. If you haven’t heard of him, George had enormous influence on Western culture, politics and theatre from the 1880s until his death, aged 94, in 1950.

The Dublin-born writer’s best known work is his 1913 play, Pygmalion, the inspiration for My Fair Lady. What isn’t so well known is that before becoming a world-famous playwright, George Bernard Shaw was a music critic for the London evening newspaper, The Star, famous for sensationalising the exploits of Jack the Ripper.

In January 1890, Shaw was covering a highbrow classical concert in St. James’ Hall, Piccadilly, when the music was overpowered by the thumping bass of an American dance band. GBS was not amused, giving what I imagine was one of the earliest anti-African-American-style music reviews we know of – a sort of pre-rock rock music review. He was, Shaw, complained:

“Inhumanly tormented by a quadrille band which the proprietors of St James’s Hall (who really ought to be examined by two doctors) had stationed within earshot of the concert-hall. The heavy tum-tum of the basses throbbed obscurely against the rhythms of Spohr and Berlioz all the evening, like a toothache through a troubled dream; and occasionally, during a pianissimo, or in one of Lady Hallé’s eloquent pauses, the cornet would burst into vulgar melody in a remote key, and set us all flinching, squirming, shuddering, and grimacing hideously.”

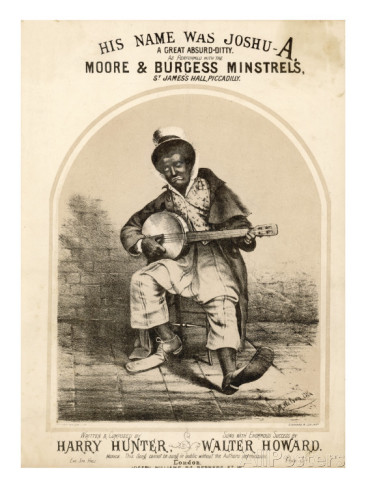

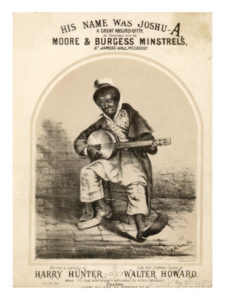

The music so disliked by GBS was performed by a quadrille or dance band working for the Moore & Burgess Minstrels, an American blackface extravaganza with its roots in the now maligned Christy Minstrels. Such was the popularity of American minstrelsy in Britain in the nineteenth century, this lavish show ran at St. James’ Hall, London, for an incredible 40 years. While derided these days for its politic incorrectness, we can’t ignore that blackface minstrelsy was the one and only conduit through which African-American-style music, comedy and dance reached the white mainstream.

Minstrelsy took African-American-inspired music, not just to the USA, Canada and the UK, but also to British colonies such as Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Whether Moore & Burgess employed black musicians that English winter, I haven’t been able to establish, but, by 1890, for the majority of black performers, minstrelsy was the only way the could make a living playing music.

So, who else was GBS writing about in his review? Louis Spohr was a German composer and classic violinist who also invented the violin chin-rest. Hector Berlioz was a French romantic composer, while Lady Halle was the eminent Moravian (Czech) violinist, Wilma Neuda, who married into the establishment.

Talking of eminent classical performers marrying into nineteenth century British establishment, the American operatic soprano, Lillian June Bailey, also married a title, becoming Lady Henschel. Lillian June, however, delighted with the music of the Moore & Burgess Minstrels. Around the same time as George Bernard Shaw’s outing, the American Lady Henschel, and her daughter were in St. James’ Hall, listening to the Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim.

But then they heard what they described as “rhythmic gay sounds, thumping and shimmering away in a most enlivening manner.” So the girls abandoned the sedate sounds of Joachim’s violin and went next door to enjoy the rocking Moore & Burgess Minstrels.