FIRST EVER MENTIONS OF THE BLUES

AMERICA’S GIFT: THE UNTOLD STORY OF HOW BLUES EVOLVED – CHAPTER ONE.

Long before the blues became a genre of American music, it was an expression used to describe an English frame of mind.

The word blues almost certainly derives from what people, many centuries ago, called ‘the blue devils’ – those imaginary evil spirits they believed caused depression. The superstition of thinking that humans can be possessed by malevolent spirits, of course, stretches back to pre-biblical times.

Probably the earliest printed mention of the blue devils is found in a rare volume of English satirical poetry, dated around 1599. Compiled by an anonymous ‘Gent’, identified only as R. C., many experts think this mysterious editor was Richard Corbet. The Bishop of both Oxford and Norwich, and a contemporary of William Shakespeare, Corbet was known to have been a drinking companion of another major Elizabethan dramatist, Ben Johnson. The rare book, ‘The Times’ Whistle Or A Newe Daunce of Seven Satires, and Other Poems’, preserved in the Old Library of England’s Canterbury Cathedral, describes the blue devils as, “the horrors, or remorse, that usually follows an ill course of life”. The pertinent couplet reads:

“Alston, whose life hath been accounted evill,

And therfore cal’de by many the blew devil.”

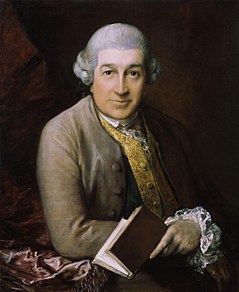

By the eighteenth century, the term blue devils had been shortened to the blues. The first time this expression appeared in written form was in a letter, written in 1741 by David Garrick, arguably the most influential of all English actors, who wrote:

“I am far from being quite well,

tho not troubled with the blews as I have been.”

Above: the first person known to put the term ‘the blues’ in writing was the ground-breaking English actor, David Garrick (1717 – 1779). Oil on canvas by Thomas Gainsborough, 1770. Courtesy: National Portrait Gallery, London.

A Georgian-era playwright, producer and theatre manager, David Garrick is the thespian credited with introducing realism into acting. London’s Garrick Theatre, opened in 1889, is named after him.

To put 1741 into historical perspective, it was the year North America’s first two literary magazines were produced. During the January of 1741, Andrew Bradford’s ‘American Magazine or Monthly View of the Political State of British Colonies’ had beaten Benjamin Franklin’s ‘The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle for all the British Plantations in America’, to print by just three days.

Also during the eighteenth century, the expressions ‘funk’ and ‘blue funk’, meaning a state of fear or panic, were being used in England for the first time. Such descriptions were first noted in 1743 at Oxford University, where the expression possibly came from the students’ slang for the blue fug of clay-pipe tobacco smoke filling their rooms. Tobacco, of course, was the engine then driving the economies of such American colonies as the Virginias and Carolinas. Another theory is that funk came from the Flemish for fear, ‘fonck’.

By the early nineteenth century, both the blues and blue funk had reached the USA, as descriptions for depression or melancholy. In 1850, the first song to feature blues in its title, according to Peter C. Muirs’ book, ‘Long Lost Blues’ (2010), was published in New York.

Entitled ‘I Have Got The Blues To Day’, this comic parlour song about getting drunk was composed by Gustave Blessner, with non-blues-like lyrics from Miss Sarah M. Graham and a chorus that went:

Then I was gayest of the gay,

But I have got the blues to day:

Then I was gayest of the gay,

But I have got the blues to day.

By now, the old English term the blue devils had also crossed the Atlantic, becoming associated in America with the delirium and tremors caused by alcohol withdrawal, the shakes we now call the DTs. Were these, then, the type of blues the composer of I Have Got The Blues Today referred to: the blue devils? You’ll find the sheet music cover of this comic ballad on the following page.

What blues was not associated with, in the mid-nineteenth century, was music. There is good reason for this. Until the term ‘blues’, referring specifically to music, first appeared in print in America in 1910, any musical forerunners to the songs and instrumentation today known as blues went under a host of other names. If such a musical forerunner was the exuberant piano sound that evolved in the African-American work camps of Texas in the 1870s, that music may have been called Fast Texan or barrelhouse, or a variety of other names depending on what area of the United States the pianist came from. Such piano music ultimately ended up being called boogie woogie. That’s boogie woogie, without a hyphen, according to those Texan experts who know such things.

Between the end of the Civil War and the early twentieth century, music we now call the blues was performed under a number of names. Some people would say they were playing ‘reels’. Others would play ‘jigs’, ‘rags’ or even describe their performances as ‘ballets’. Rural musicians, black and white, played such folk music individually, on violins, banjos or, later, guitars. Or such instruments were played in unison, in trios or quartets, perhaps with a singer.

Whenever this music was heard in the early twentieth century by educated Americans, black or white, or observed by anthropologists or musicologists, it was usually, quite simply, referred to as American folk music.

To find out more about the amazing evolution of the blues, check ‘America’s Gift’, my big blues paperback at goo.gl/At5AZe; my eBooks ‘How Blues Evolved 1&2’ at Amazon or my blues videos at goo.gl/UQ8id8