Blues, booze, drugs and religion.

Oh, the irony! White evangelists peddled drugs and booze, as black families feared the blues.

When it comes to blues, booze, drugs and religion, this is a world laced with irony. In the early days of blues, black families, steeped in a century of Christianity, worried sick about sons, daughters and grandchildren playing what they called the devil’s music, which was the dreaded blues, of course.

Remembering the 1880s, the famous blues pioneer who standardised blues into 12-bars, W.C. Handy, wrote in 1949, of buying a guitar as a teenager and taking it home to where he lived with his parents in Florence, Alabama. His father saw the instrument and immediately spat the dummy.

“A guitar, one of the devil’s playthings. Take it away. Take it away, I tell you. Get it out of your hands. What possessed you to bring a sinful thing like that into our Christian home? Take it back where it came from.”

Chastised, Handy switched to learning the trumpet instead. Much more recently, in the late 1920s, the good African-American Christian’s fear of the blues hadn’t evaporated.

Said the 1940s and 50s blues great, Muddy Waters, in Robert Gordon’s Muddy biography, Can’t Be Satisfied:

“My grandmother told me when I first picked that harmonica up, she said, Son, you’re sinning. You’re playing for the devil. Devil’s gonna get you.”

Now here’s the irony of the situation. Good Christians worried that their blues-playing children would get mixed up with drugs, alcohol and loose women, amongst other things.

Yet, at the very time these views about blues and the devil were taking shape, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, American evangelists (white ones, admittedly) were going around the world hitting their converts with a mixture of opium and alcohol.

Blues hadn’t been named as such – all its various strains were still hanging in the air under various names like jig, reel, rag, ballet and the obnoxiously named coon song. For some reason, as far as I know, neither whites nor blacks ever suggested coon songs were the work of the devil – another irony.

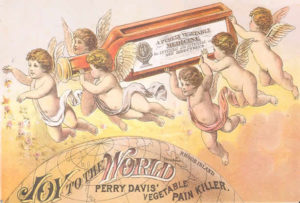

Nor did anyone in the nineteenth century ever think a medicine, named and trade-marked as America’s first nationally-advertised pain relief, was the work of the devil. This was Perry Davis’ Pain Killer. Introduced to the public in 1843 by a devout Baptist, Perry Davis of Providence, Rhode Island, USA, Perry’s Pain Killer potion was patented in 1845.

As a registered trade brand name, there was no legal requirement to put its ingredients – opium and alcohol – on the bottle. During the American Civil War, Perry Davis’s Pain Killer was given to both soldiers to keep them fighting longer and horses to make them work longer and harder.

As a registered trade brand name, there was no legal requirement to put its ingredients – opium and alcohol – on the bottle. During the American Civil War, Perry Davis’s Pain Killer was given to both soldiers to keep them fighting longer and horses to make them work longer and harder.

Widely regarded back then as a ‘wonder drug’, Perry Davis’s Pain Killer was distributed by American missionaries around the world during the nineteenth century. In America, the brand ran multiple print ads like the one above right, including text only advertising that appeared in The Baptist Missionary Magazine during the 1880s. The largest ads ran the headline ‘Joy to The World’ suggesting the potion delivered heavenly relief from pain, around the world. Mind you, that’s not too false a claim. A powerful ‘vegetable’ mix of opiates and ethyl alcohol, Perry Davis’s Pain Killer would do the trick for any number of ailments as would that other wonder drug of the nineteenth century, heroin. It’s name was a play on ‘heroic’ which people thought it was.

One missionary in Burma (Myanmar these days), New Yorker Marilla Baker Ingall, even had a Perry Davis’s Pain Killer sign displayed on a tree outside her mission. In 1897, Baker Ingall wrote how such analgesics “are a blessing to Burma and go packed off with our Bible and tracts”. No wonder she had Buddhists converting to Christianity, not only in Burma but in China and all through South East Asia.

Now, as we know, the missionaries weren’t peddling their mix of opium and hard liquor back then out of malice. Just as the God-fearing black families didn’t fear blues simply to spite their youngsters’ musical ambitions. It was all done from ignorance at a time when the whole world was ignorant about a lot of things.

In many ways, it still is.