The Album That Changed The World.

The Album That Changed the World

Below is a terrifically perceptive article just written by my old friend, blues guitarist and songwriter, John Phillpott, for World Music Central, your connection to traditional and contemporary world music. Link to the latest edition of World Music Central here: ARTICLES.

Nearly 60 years ago, in the spring of 1964, an emerging London rhythm and blues band released their first album. It was an event that not only kick-started a revolution in the planet’s music-listening habits, but also sowed the seeds of what would become known as world music. Here’s how it all started.

Back in the summer of 1967, The Beatles released a much-awaited album to great public acclaim. All right, you can probably guess what’s coming. For it’s now more or less universally accepted that after Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, nothing would ever be the same again.

Oh yes indeed. It was the groundbreaker, a total departure from what had gone before, the faces on the sleeve launching a thousand musical ships, both good, bad… and some downright ugly.

Yes, we all bought concept albums, not all of them good, didn’t we? All these years later, who knows what embarrassments still lie awaiting detection in those dusty record racks.

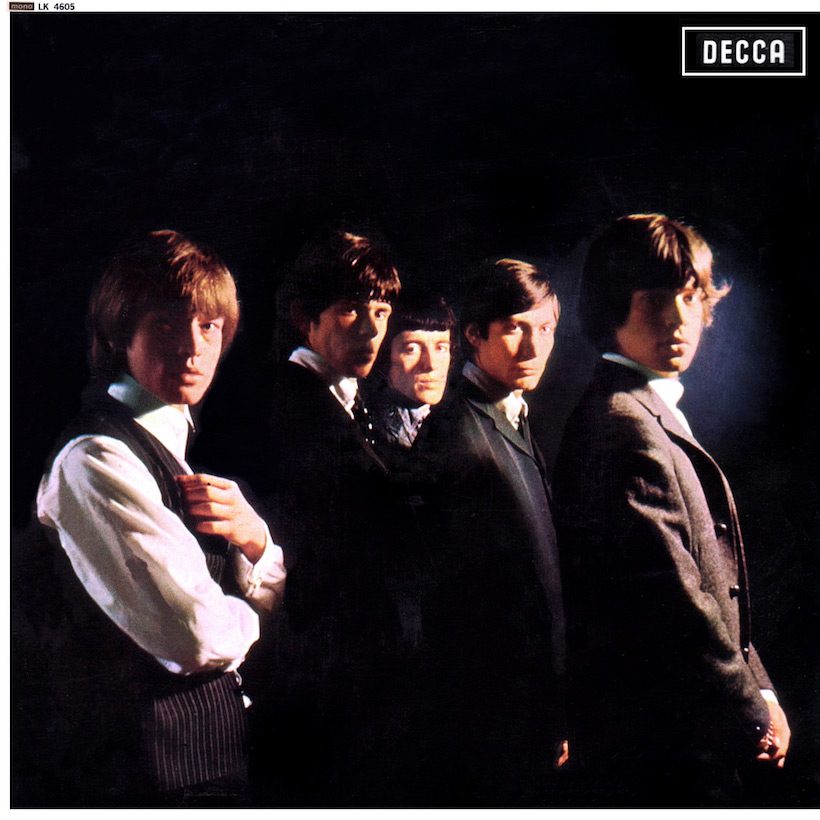

However, a mere three years before, an even greater and more significant slice of vinyl had hit the streets, a disc that – in my view – would represent the opening shots in a listening revolution that, over time, went on to completely change not just our musical tastes, but how we might regard the very planet itself. The album was simply called The Rolling Stones. And it would lay the foundations of a burgeoning interest in a music form virtually unknown outside the United States of America which – in turn – would go on to whet an insatiable appetite for what is now known as World Music.

The history is familiar enough. Five blues-mad young men scuffling gigs around the London area had just been awarded a record contract by the Decca company – the same organisation that had disastrously and so memorably turned down The Beatles only the year before.

Decca was determined not to make the same mistake again. The Rolling Stones may not have had the same cache as the Moptops, but judging by their growing popularity in and around Britain’s capital city, better safe than sorry. That must have been the thinking at the time.

It was a wise move for success quickly followed. The release in June 1963, of the Chuck Berry cover “Come On” was quickly followed by “I Wanna Be Your Man,” a Lennon-McCartney composition, and then “Not Fade Away,” a Buddy Holly throwaway tune that the boys reimagined with Brian Jones’ urgent, wailing harmonica, and a heavier Bo Diddley beat than the original. The die was cast.

Up until now, British audiences had become used to The Beatles covering what were then obscure American rhythm and blues songs. The band had learnt these from imported records, which thanks to visiting American sailors, had become readily available in their hometown of Liverpool. But there was a yawning stylistic chasm developing between the set lists of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. Whereas the former gave most tracks a softer, three-part harmony Everly Brothers-style treatment, The Stones’ music was much closer to the originals.

For while the Beatles’ cleaned up, and slightly sanitised ballads that told of romantic, idealised love, the Stones sang about let’s-get-down-to-it sex. But there was more to it than that – the latter’s renditions were far more authentic and much closer to the original versions. And it was precisely because of the band’s insistence on cultural and musical accuracy that the building blocks of an interest in what would later become known as World Music began.

Let’s look at some of the seminal numbers included on that first album that would go on to create not just a legion of young fans, but also inspire many of them to investigate further. In other words, to go out and discover the originators and their music. So, in a thousand and one adolescent bedrooms, each equipped with a green or red Dansette record player, it was a case of let’s get in the groove and start the quest…

Just who is Slim Harpo (I’m A King Bee)? And these guys, Willie Dixon and the fantastically named Muddy Waters, too (I Just Want to Make Love to You)? Where is Route 66? Is that a road, or what? And why was Bobby Troup so fascinated by whatever it was – or is – to write a song about it? What do those nonsense lyrics mean in Walking the Dog (Rufus Thomas/Willie Dixon)? Is there a secret message there that I’m just not getting?

And while we’re at it, does Mick Jagger’s lazy vocal on “Honest I Do” stay true to the style of the person who seems to have written that number, a guy by the name of Jimmy Reed?

Questions, questions. And, if you were curious like me, a 15-year-old adolescent daydreaming out the window in the cigarette-stub-end class of an English boys’ grammar school, you really wanted them answering.

Fired up by the weird and wonderful sounds that were so annoying one’s parents, it wasn’t long before the urge to reproduce them started to compete with those rampaging hormones in a race to establish superiority.

A diatonic harmonica, as recommended by Brian Jones, was bought from a local music shop. For quite some time, nothing I blew sounded like the records I so admired, rather end-of-trail trills and warblings wheezed by a cowboy who’d just arrived back at the bunk house after a hard day on the range.

A cheap guitar followed. Then the sore finger ends and, at long last, the ability to fret a few chords without muffling any of the constituent notes. Day by day, month after month, and despite all the odds, like so many of my generation, I became reasonably proficient at both instruments.

This article’s author, John Phillpott, blows his blues harp.

One development followed another. This was the eternal learning curve that was the 1960s, a portal of light in the darkest and most war-torn century in the history of Mankind, a beacon that beckoned the faithful pilgrim ever onwards. But perhaps most of all there were the endless discoveries of black artists who were known only within their respective communities.

In the big American cities there were Junior Wells; Elmore James; Muddy Waters; Albert, Freddie and B.B. King; and Howling Wolf. Yes, this was indeed the journey of a lifetime. Playing country shacks called juke joints we met the likes of Lightnin’ Hopkins, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Arthur Crudup, and in Al Capone’s Chicago, we came across piano players such as Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis.

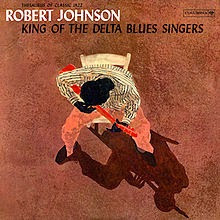

But perhaps the greatest prize of all was the discovery down at the crossroads of Robert Johnson, the great Delta blues guitarist.

The only existing photograph of Robert Johnson.

Nevertheless, for me, this was only the start of my lifetime’s mission. Elsewhere, my curiosity only increased. Probing ever deeper and deeper into the origins of the Nashville country music sound, myself and fellow travellers found ourselves in the Appalachian Mountains, where the folk memory reached back to 17th and 18th century England, Ireland and Scotland.

Songs like ‘Barbara Allen,” “The Gypsy Davie,” “John Hardy,” “The Unfortunate Rake,” reinvented as “The Streets of Laredo” and “St James Infirmary.” And fiddle tunes from the other, more distant mountains that lay across the great ocean, such as “Miss McLeod’s Reel,” “Soldier’s Joy” and “Brighton Camp.” The former would undergo a metamorphosis and become known in the Southern hills as “Uncle Joe”; the latter better known as “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” a tune that would be granted new life courtesy of John Ford’s western epics.

And here’s another thing. Most aspiring rock and roll artists of my generation heard Chuck Berry thanks to Keith Richards long before we savoured the real thing via the great man himself. And so, yet another door opened, one that led me away from the stuffy school classrooms of spring, 1964, and into the new, brightly lit cavernous halls of magical music and endless possibilities.

However, the desire to find out more about the musical world beyond the confines of our Dansettes had only just begun. This was a slow kindling that would soon spread like a forest wildfire. After hearing Bob Dylan, we became eager to investigate his mentor, Woody Guthrie, and soon discovered that the ultimate in stylistic imitation was most surely the sincerest form of flattery.

In turn, the music of the British Isles came under the microscope. Scottish fiddle and English concertina tunes, the unaccompanied repertoires of elderly Dorset or Warwickshire farm labourers, the archived legacies of collectors such as Cecil Sharp… all this rich seam of knowledge was mined to further one’s enjoyment and knowledge.

Then during the early 1970s our hunger was further satiated by the recordings of Ry Cooder. The former guitarist with The Rising Sons and Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band became, over a series of momentous recordings, the greatest musical anthropologist on the planet, selecting hitherto obscure songs from the American folk songbook, and making them his very own.

Around the same time, enthusiasts on both sides of the Atlantic began talking about ‘roots’ music. Here was a common language, understood by the faithful. Cooder may have been the high priest, a conduit to this secret world, but upon reading the musical credit for a given number, the next task for the converted was to seek out the original.

Of course, Cooder’s long and illustrious career as a musician and folklorist speaks for itself. But even more important, his work allowed so many others a voice, men such as the renowned Tex-Mex accordionist Flaco Jiménez, whose career was given an immeasurable boost.

Ry Cooder went on to work with African and Indian musicians, but perhaps most significant of all was his collaboration with Ibrahim Ferrer and the Buena Vista Social Club musicians of Havana, Cuba. Once again, the interest was already in place. The record-buying and gig-going public had developed a taste for regional music forms, and so an eager market was positioned out there, ready and waiting to snap up the latest goodies on the world music stage.

Today, that process continues to flourish and expand, as successive generations are introduced to new cultures and methods of music-making. But had it not been for those 12 inches of vinyl, hurriedly recorded back in 1964, I doubt very much that any of this revolution in sound would have occurred. For in my estimation, it was the evangelical enthusiasm of a bunch of British blues freaks, collectively known as The Rolling Stones, an almost unbelievable 60 years ago, that caused such a seismic shift in listening habits.

Otherwise, the music-loving public might well have been obliged to permanently content itself with just The Beatles, Cliff Richard, and Elvis Presley. Perhaps there’s nothing wrong with that. After all, they were all fabulous performers. But just think what we would have been missing down all these years had not the Decca recording company, fearful of making another huge mistake, took the chance to sign a group of five musicians who would be musical midwives to that global movement in sound now known as World Music.

Author: John Phillpott

English musician, author and journalist, John Phillpott, has written for many newspapers and magazines during a career that spans more than 50 years. His latest book Go and Make the Tea, Boy! is a memoir of his days as a young reporter.