Rocking five continents.

Rock ‘n’ Roll Myths six and seven.

“It’s very hard to tell what made me first decide to play the guitar. ‘Rock Around the Clock’ by Bill Haley came out when I was ten, and that probably had something to do with it.”

David Gilmour, Pink Floyd.

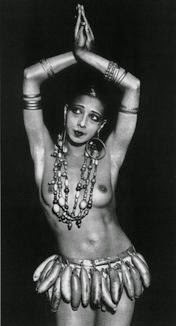

In 1955, Bill Haley and His Comets unlocked the pop world’s music charts with ‘Rock Around the Clock’, opening the door for that first wave of American rock ‘n’ roll performers to flood through. Those early names still resonate today: Bo Diddley, Buddy Holly, Carl Perkins, Chuck Berry, Eddie Cochran, Elvis Presley, Fats Domino, Gene Vincent, Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard (cover pic), to name ten.

Six of the ten were white, and four black: Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino and Little Richard. Such a comparatively even racial balance was unusual in an era when most hit records were by white artists. For the first-time, acts of different colors (and persuasions) were charting nationally in the USA and around the world with their own style of music. Previously, black artists, say Nat King Cole or the Ink Spots, basically had to reproduce the era’s urbane white musical styles to achieve chart success. For the first time, especially in the USA, skin color was becoming irrelevant to record buyers, radio listeners and concert goers. And not just in the way young whites were suddenly listening to black music. Bill Haley’s ‘Rock Around the Clock’ also went to number three on Billboard’s black R&B chart. Blacks were buying white music as well.

At the beginning of 1956, a Decca official described ‘Rock Around the Clock’ as “the biggest Decca record since Anton Karis’s movie soundtrack ‘The Third Man’ theme”, which spent 11 weeks atop Billboard’s best-sellers chart in 1949, selling some 40 million records by combined artists. Highest overseas sales for ‘Rock Around the Clock’, Decca’s man said were in England, Germany and Australia, followed by Norway, Sweden, Brazil and Japan[1]. Rock ‘n’ roll was making it big on five continents. How international was that?

But let’s backtrack to 1951 when Ike Turner’s band recorded ‘Rocket 88’ in Memphis, Tennessee, and Bill Haley cut the same song in Philadelphia. In Cleveland. Ohio, that year, as legend has it, disc jockey Alan Freed coined the term ‘rock and roll’ on his radio show.

Rock Myth 6. Rock ‘n’ roll was a term coined by DJ Alan Freed?

This is a well-worn myth many people still think is true. Alan Freed, often called ‘The Father of Rock and Roll’, was a white radio disc jockey born in Pennsylvania in 1921. According to myth, Freed coined ‘rock and roll’ on Cleveland radio in 1951. We’re splitting hairs here, but Freed actually used the term first in 1949, deejaying on a radio station in Akron, Ohio, 40 miles away. As Akron’s top disc jockey, Freed was befriended by Leo Mintz, who owned Record Rendezvous in Cleveland, one of the larger city’s top record stores. Mintz was unusual in being white, yet selling black blues and R&B records which, he told Freed, had his store’s young white customers jiving in the aisles. As the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History explains:

“In the late 1940s, Mintz saw the decrease in jazz and big band records. He realized his young customers would dance around his store when a rhythm & blues record was played. To break the taboo of white people listening to black music, he called it ‘rock ‘n’ roll’, borrowing from old blues lyrics. He convinced a young WAKR-AM disc jockey, Alan Freed, to play a rock ‘n’ roll record as a novelty song on his program in 1949.”

Cape Western Reserve University’s Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

As you’d expect, playing black music on white radio in 1950s America caused outrage. Freed was immediately fired, then rehired after fan mail flooded in from young white listeners saying how much they loved the discs he spun. But terms like ‘blues’, ‘race music’, and ‘rhythm and blues’ were anathema to Cleveland society: white and black. Aghast white parents looked down their noses upon such music. Respectable God-fearing black parents thought it ‘devil music’. To placate them, it’s said Mintz suggested Freed called the music rock ‘n’ roll, thus avoiding the stigma associated with black music. The genre took off from there.

According to rock historian, John Jackson, in his book ‘Big Beat Heat’, Freed wanted nothing to do with playing black music at first. “Are you crazy?” Freed argued. “These are race records.” Luckily for Freed, Mintz talked him round. Both having Eastern European Jewish backgrounds, Alan Freed and Leo Mintz soon became friends. In July, 1951, sponsored by Record Rendezvous, Alan Freed began his Rock & Roll House Party on Cleveland radio. Mintz supposedly sat next to Freed in the studio, handing him records.

While Freed didn’t invent the term rock ‘n’ roll, he was the first radio disco jockey to use it, and he was instrumental in making rock ‘n’ roll famous throughout the USA and in Europe. Though a comparatively elderly 31, Freed peppered his radio show with 1940s jive-talk, popularizing words like ‘cool’, ‘cats’, ‘daddio’, ‘teenager’ and ‘hep cat’. Oldies were ‘square’, teenagers ‘hep’ or ‘hip’. “Yeah, daddy,” Freed would say, “let’s rock and roll.”

Fact: While Alan Freed didn’t coin the term, rock ‘n’ roll, he certainly popularized it.

While we’re on the subject of Freed’s jive talking, let me slip in my myth number seven.

Rock Myth 7. Calling music lovers ‘cats’ began with Alan Freed in the 1950s.

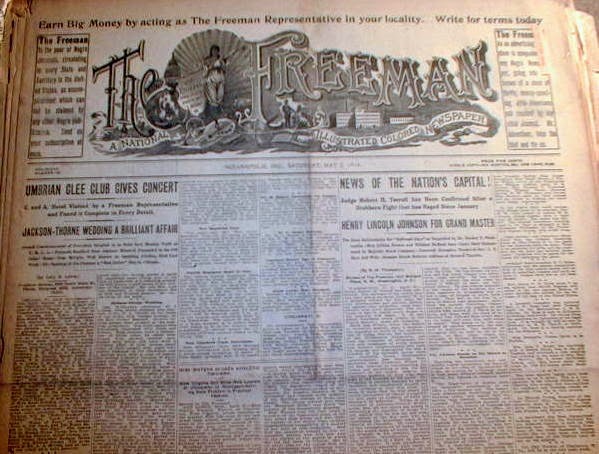

You’d be forgiven for thinking the term ‘cat’ for hip music lover originated with Alan Freed and his radio jive-talking; or perhaps in America’s 1940s bebop era, when ‘cat’ was a term Alan Freed might have heard on black radio. Hep cat, for example, was described in 1938 by influential Harlem bandleader Cab Calloway as, “a guy who knows all the answers and understands jive (jazz)”. But ‘cat’ (one of Rolling Stone Keith Richards’ favorite words for musician) is a term at least 28 years older than Cab Calloway’s definition, as seen in this 1910 Memphis concert review[2] in The Indianapolis Freeman, America’s leading African-American newspaper:

“Mr. Kidd Love is cleaning up with his ‘Easton Blues’ on the piano. He is a cat on the piano”.

The Indianapolis Freeman, 16 July, 1910.

This 1910 newspaper review (above) seems to be the first time known that the fledgling term ‘blues’, referring to music, ever appeared in print. I’d also bet Kid Love was playing what we call today boogie woogie piano, the bedrock of rock ‘n’ roll, which we’ll examine more fully later.

Very little is known of Kidd Love, a black vaudevillian from Mobile, Alabama, except from this advertisement seeking a manager for H. Love and his wife, Gussie, in the Indianapolis Freeman of June 24, 1911.

H. KIDD & GUSSIE LOVE.

Those Two Entertainers In “ONE”. Open to hear from all first-class managers. Only original compositions sung by this team. Neat Costumes. 15 Minutes of Furious Fun. WE BOTH WORK UNDER CORK. YOU CAN GUESS THE REST.

Address all Communications to THE LOVES, Care of Goat’s Club,2708 State St. Chicago, Illinois.

Advertisement appearing in The Indianapolis Freeman in 1911.

Fact: Calling hip music people cats started as early as 1910

[1] Jack Doyle. Rock Around the Clock – Bill Haley, PopHistoryDig.com – March 17 2016.

[3] Rock Around the Clock was originally titled, We’re Gonna Rock Around the Clock. It then became (We’re Gonna) Rock Around the Clock before being called simply Rock Around the Clock.

[2] The Kid Love review first appeared in Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff’s essay in 2008’s ‘Ramblin’ On My Mind: New Perspective on the Blues’. The advertisement above features in Abbott and Seroff’’s 2017 book, ‘The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African American vaudeville’. Gussie was Love’s wife, and ‘working under cork’ meant working in blackface. Black vaudeville entertainers, not only whites, darkened their faces using burnt cork in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.