The song that introduced blues to the world

tune, “St. Louis Blues”, has popped up on this site a number of times recently.

Perhaps, subliminally, it’s because I know it was first published 100 years ago,

in 1914.

|

| One of many St. Louis Blues sheet music covers |

regarded as the tune that

Handy is most remembered for. First recorded as an instrumental in New York in 1915,

the track was then released the following year in England, before anywhere else

in the world. From England in 1916, “St. Louis Blues” spread across the

English-speaking world: to Australia, New Zealand, Rhodesia, South Africa and

Canada. From Canada, undoubtedly, the record found its way back to its homeland

– the place of its original recording – the USA. That was just the record, of

course. The sheet music of “St. Louis Blues” had sold in America like

gang-busters with hundreds, if not thousands, of American bands from 1914

onwards playing the new blues tune, coast to coast. And don’t forget that its

composer, W.C. Handy himself, with his orchestra, would have been playing “St.

Louis Blues” live wherever they were appearing in the States. I’ve written

before that Handy sold away the rights to his first composition “The Memphis

Blues” for $100. He wouldn’t make the same mistake again and subsequently built

his successful publishing company on the success of “St. Louis Blues”.

|

| Blues composer and bandleader, W.C. Handy, blowing up a storm |

instrumental, “The Memphis Blues”, became the first blues ever recorded, Handy played

“St. Louis Blues” in public for the first time. Describing that 1914 moment in

his autobiography, Handy wrote: “The one-step and other dances had been done to

the tempo of Memphis Blues … When St. Louis Blues was written the tango was

in vogue. I tricked the dancers by arranging a tango introduction, breaking

abruptly into a low-down blues. My eyes swept the floor anxiously, then

suddenly I saw lightning strike. The dancers seemed electrified. Something

within them came suddenly to life. An instinct that wanted so much to live, to

fling its arms to spread joy, took them by the heels.”

And for the first ever blues recording by black musicians, here’s the link again to Ciro’s Club Coon Orchestra’s rendition of St. Louis Blues recorded in London in 1917.

In an

article about the significance of the blues written in 1919, Handy wrote:

“Blues music was

|

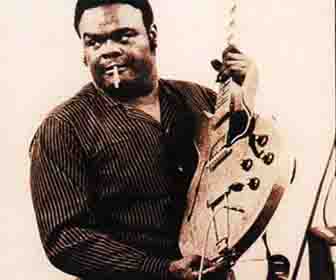

| Jamaican Dan Kildare was first black to record blues |

created to chase away gloom. It is of negro origin and must

pertain to a negro life. I am a southern negro by birth and environments and it

is from the levee camps, the mines, the plantation and other places where the

negro laborer works that these snatches of melody originate. The negro laborer

does his best work while he sings. I have heard on the Mississippi plantation

the negro plowman, after a day’s work which began at sunrise, sing just these

little snatches, ‘Hurry, sundown, let tomorrow come,’ which means that he hopes

tomorrow will be better than today. It is from such sources that I built my St

Louis Blues which begins, ‘I hate to see the evening sun go down’.”

group of black American musicians working in England, led by the Jamaican

bandleader, Dan Kildare, recorded the first version of “St. Louis Blues” to

feature vocals. This was a recording of enormous significance. Not only was it the

first African-American recording of the blues (the band was African-American),

it was the first black blues vocal ever, even if the vocalist was Dan Kildare’s

brother, Walter, another Jamaican. If you’d like to hear this recording, check

The World’s First Black Blues Recording (21 December 1913) in my archives.

record “St. Louis Blues” in the United States was a white blues singer who did

a lot of work for W.C. Handy called Al Bernard. Born in New Orleans in 1888,

and known as both The Boy from Dixie and The Singing Comedian, Bernard had a

sweet singing voice that could pass as female. Bernard’s recording of “St.

Louis Blues”, on the Victor label in 1917, was described by W. C.

|

| Al Bernard: blues and western swing pioneer |

Handy as “sensational”.

Crazily, an African-American performer still wouldn’t cut a blues in America

until Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” in 1920.

(and the song’s) popularity, he recorded nine versions of “St. Louis Blues” for

nine different record labels. His other recordings included the Baby Seals

ragtime number, “Shake, Rattle & Roll”.

nothing is new in rock & roll, Al Bernard preceded bands like the Rolling

Stones by over 50 years when he recorded “Satanic Blues” in May 1921, with the

Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Bernard’s 1930 recording of “Hesitation Blues”,

incidentally, is also described as one of the earliest examples of western swing.

Blues” we’re talking about here and it’s “St. Louis Blues” we’ll finish

the tune is most commonly said to have been an African-American woman singing the

melody in St. Louis while lamenting her husband’s absence. The late American

writer, Robert Palmer, put the date at 1892, although this seems unlikely,

since Handy himself said he first heard blues in 1903.

the jazz and blues great, Louis Armstrong, 55-years-old, made his debut with

|

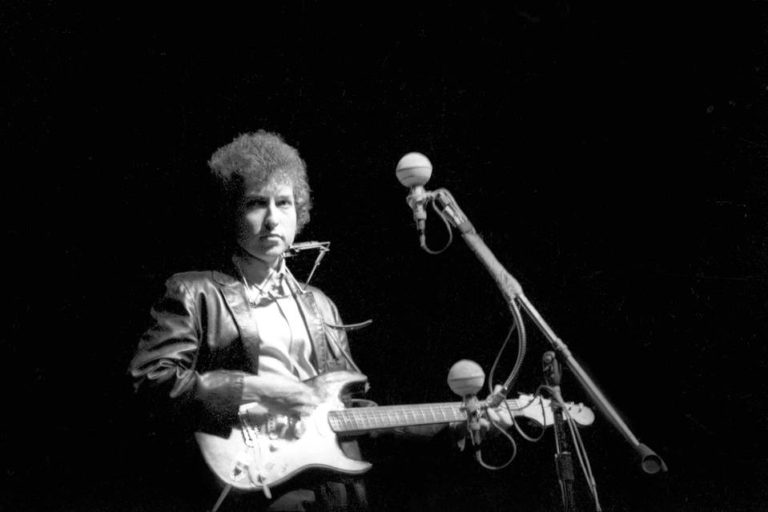

| Louis Armstrong |

the New York Philharmonic Orchestra playing “St. Louis Blues” in New York’s

outdoor Lewisohn Stadium. Armstrong must have played the song a thousand times,

originally on his cornet and then on his trumpet, and recorded over 40 versions

of “St. Louis Blues” between 1925 and his death in 1971. But this time, it was before

22,500 people, with 10,000 having been turned away. Leonard Bernstein was

conducting and in the audience was the famous song’s distinguished composer, W.C.

Handy, now aged 82. It’s said that Louis Armstrong made his horn sound even

more poignant than ever on that hot July night. And captured on television was

a close up of old William Christopher Handy dabbing tears from his eyes with a handkerchief.

mentioned New York Philharmonic Orchestra, allow me to indulge in another piece

of old blues trivia. The third version of ‘The Memphis Blues’, the third blues disc ever recorded,

was cut in October 1914. Performed by the all-white New York Philharmonic Orchestra, it featured vocals by Morton Harvey, a 28-year old white

vaudeville star from Nebraska. Harvey freely

admitted later that, apart from the trombone, the orchestra

|

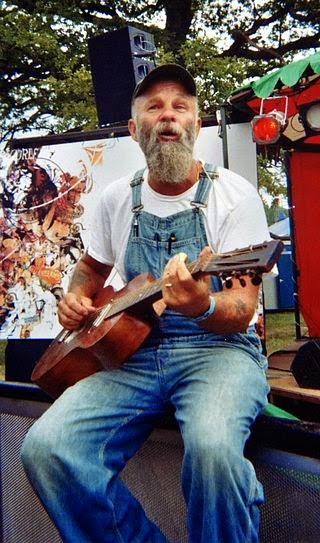

| Even Big Bill recorded St Louis Blues |

accompanying him

didn’t quite capture a blues feel.

“It wasn’t their fault,” Morton Harvey wrote in 1953. “The ‘Blues’ style of singing and playing, which

became so familiar later, was just about to be born.”

blues and its many origins can be found in my “How Blues Evolved” eBook, packed

with pictures and available now via the following links.

In the UK, preview How Blues Evolved on this link below:

In the UK, preview How Blues Evolved on this link below:http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Ddigital-text&field-keywords=how+blues+evolved+volume+one

"Mr. Handy wrote the now world-famous 'Memphis Blues'" — _The Crisis_, 11/1915. "'The St. Louis Blues' took even longer to catch on with the general public [in the 1910s] than did 'The Memphis Blues'…. Although 'Memphis Blues'… remained popular [in the 1920s], 'St. Louis Blues' was beginning to move out front…." –_Lost Sounds_ by Tim Brooks.

Thanks for your comment, Joseph. You'll see that the post you refer to, "The song that introduced blues to the world", does say that Handy's 'The Memphis Blues' was the first blues ever recorded, in 1914. Elsewhere on my blog (and in my book, 'How Blues Evolved') I reiterate many times that The Memphis Blues was the third of three blues published in 1912. These were the first three songs named, published and marketed specifically as blues.'The St. Louis Blues' was first published in 1914, two years after The Memphis Blues. It was recorded in the USA in 1915 but not released.