Updated 20 July 2016

|

| St. Louis’ famous Gateway Arch is 630 ft. or 190 m high. In the nineteenth century, St. Louis used to be called The Gateway to the West |

St. Louis, Missouri, is a city so steeped in the blues, even the local NHL ice hockey team calls itself after one of the most famous blues songs of all time. They wear blue, naturally, and the tune they’ve taken for their name is probably the most famous blues tune of all, ‘St. Louis Blues’. It’s certainly one of the most recorded blues of all time, recorded by everyone from Bessie Smith (backed by Louis Armstrong), to Chuck Berry and Stevie Wonder (not together I might add).

As with most famous blues songs, there are conflicting legends about how St. Louis Blues came to be written. The best story about its birth starts in 1892. Will Handy, then an out-of-work young cornet player, aged 22, chanced upon a woman on the St. Louis waterfront lamenting her absent husband.

|

| W.C. Handy photographed in 1892, the year he witnessed blues guitarists playing in St. Louis |

“My Man’s got a heart like a rock tossed in the sea”, she sang. Handy, later included the line, and the woman’s melody, in a memorably sad song he wrote back home in Memphis, where he published St. Louis Blues in 1914. This was also the year blessed by the release of the first known blues recording, another famous W.C. Handy (as he later came to be known) composition, The Memphis Blues’.

W.C. Handy also wrote in his 1949 autobiography how he heard some of the first blues guitarists ever reported, while bedding down on the St. Louis Levee. “While sleeping on the cobblestones [on the levee] in St. Louis (1892), I heard shabby (Negro) guitarists picking out a tune called ‘East St. Louis’. It had numerous one-line verses and they would sing it all night.”

In a field as vast and unsubstantiated as blues, there are always going to be a host of claims and counterclaims as to what song came first. However it’s a musical fact that the sheet music of Hart Wand’s ‘Dallas Blues’ went on sale two years earlier (than St. Louis Blues), in 1912, and remains, officially, the first blues published. Even so, from St. Louis’ point of view, a song called ‘One O’ Those Things’, by James Chapman and Leroy Smith, published in St. Louis in 1904, is oft cited as the first published song with a 12-bar section.

|

| Published in 1914, this is probably the world’s best known blues song |

However, since One O’ Those Things is listed as a ragtime two-step, it is not classified as a blues. And there, as far as officialdom goes, lies the difference. The song St. Louis Blues, however, does hold one notable, if little known, record. The version recorded in London in 1917, by Ciro’s Club Coon Orchestra, a group of African-American musicians led by a Jamaican, based in England in World War One, was the first ever blues recording by black artists. The blues in St. Louis, though, goes back much further than 1914 or 1917.

Back in the 1870s, America was in the midst of a jig-fest. So many styles of jig were being performed, it is impossible to name them all. Some early twentieth century musicians have said what they called jigs were what we now call blues. In St. Louis, however, jigs took on a new lease of life when a new style of piano-playing was developed there called ‘jig-piano’. Other jigs and reels in the area evolved into southern cakewalks and then into a separate stream of ragtime to the regular eastern stream, called Missouri or classic ragtime. This high-end style was made famous by pianists like Scott Joplin (1868-1917) whose 1899 sheet music hit, ‘Maple Leaf Rag’, was the first named rag published by a black artist.

As we know, ragtime was a direct descendant of the blues. In those days, though, rags and ragtime could also be called cakewalks, polkas, two-steps or marches. Anything went when it came to musical labels. No names were fixed in the 1890s. The genres would only be defined years later.

A clue to another style of music happening in St. Louis back in the late nineteenth century, comes from E. Simms Campbell in his book, ‘Jazzmen’. In 1939, Campbell wrote how the Negro piano players of Texas played an early form of boogie woogie often referred to as a ‘fast western’ or ‘fast blues’, “as differentiated from the ‘slow blues’ of New Orleans and St. Louis”.

|

| St. Louis’ Eva Taylor with her husband, Clarence Williams |

The murder ballad, ‘Frankie and Johnny’, is supposed to take its theme from a killing in St. Louis in 1899, although the actual tune can be traced back to the American Civil War.

One of the most famous early blues divas to come out of St. Louis was an African-American singer called Irene Gibbons who would become famous as Eva Taylor, billed as ‘The Dixie Nightingale’. Born in 1896, Irene was so talented she was touring in stage reviews at the age of three and, by her teens, had toured extensively in vaudeville around the world including to Europe, New Zealand and Australia. By 1922, Eva was on stage in Harlem and cutting blues records for the Black Swan label. She continued to record blues, jazz and pop through the 1930s. Eva, who also performed under her real name, was one of the first African Americans to appear on radio during the 1920s and was vocalist for her husband Clarence Williams’ famous Blue Five band of the early 1920s, featuring such jazz and blues luminaries as Sydney Bechet, Louis Armstrong and Coleman Hawkins.

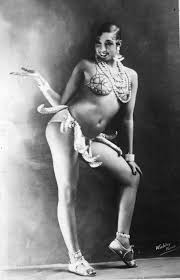

Another famous African-American performer who started life in St. Louis, was Freda MacDonald, born in the city in 1906. A one-time St. Louis street urchin who made money dancing to blues and ragtime on St. Louis’ street corners, Freda would later become world famous as Josephine Baker, aka the ‘Black Pearl’, the ‘Bronze Venus’ and the ‘Creole Goddess’.

|

| The fabulous Josephine Baker doing her famous Banana Dance in Paris |

Recruited as a dancer to the St. Louis Chorus vaudeville show, aged 15, Josephine went to Paris around 1925 where she became a French institution as an exotic (and erotic) dancer, the first African American to star in a motion picture and one of the most photographed woman in the world. Josephine Baker may not have sung the blues, but she certainly danced to them: in St Louis anyway.

St. Louis was also the city where the most influential blues guitarist, in my humble opinion, who ever lived, Lonnie Johnson, got his start playing the blues. (Note that I said influential, not the best.) Born in New Orleans, Lonnie settled in St. Louis in 1921 and spent the next five years playing on the Mississippi riverboats. Blues legend Big Bill Broonzy remembered Lonnie and his brother in St. Louis in 1921: “I met Lonnie Johnson and his brother (James ‘Steady Roll’ Johnson’). They called him Buddy Johnson. Then Buddy was playing the piano and Lonnie was playing the violin, guitar, bass, mandolin, banjo and all the things that you could make music on, and he was good on either one he picked up and he could sing too, just as good.”

In 1925, Lonnie entered and won a blues competition where the first prize was a recording contract with Okey Records in Chicago. He was then labelled as a blues artist forever more but, nevertheless, pioneered many of the blues guitar riffs and vocal patterns we now think as standard. Check out my archives for the ‘Why Lonnie Johnson was the most Influential Blues Guitarist of all’ post of 18 June 2013.

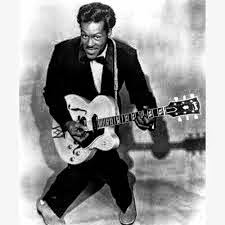

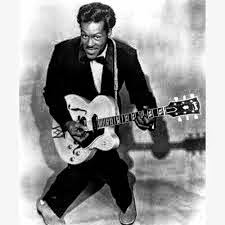

One year after Lonnie Johnson won his blues contest there, St. Louis’ most famous of all sons or daughters, was born. This just my opinion, of course, but Chuck Berry, was born at 2520 Goode Avenue, St. Louis, on 20 October 1926. As John Lennon once said, “If you tried to give rock’n’roll another name, you might call it Chuck Berry.”

|

| Rock n Roll and blues artists don’t come any bigger than St. Louis’ Chuck Berry. |

In Chuck Berry’s 1987 autobiography, he writes how he and Ike Turner were two of the biggest draws in St. Louis in the early 1950s and mentions my own early guitar hero, Albert King.

“Albert King, another guitarist from the St. Louis area who sported a left-hand guitar, began climbing to the Ike and Chuck level,” Berry wrote.

While Ike and Albert both hailed from Mississippi, they nevertheless cut their teeth in St. Louis, as did young Tina Turner from Nutbush, Tennessee. Tina moved to St. Louis aged 16, to reunite with her mother, and started frequenting the city’s clubs, where she fell under the spell of Ike Turner and his Rhythm Kings.

|

| Ike and Tina Turner in their St. Louis days, back in the 1950s frequenting the city’s clubs, |

Anna Mae Bullock, as she was then, joined Ike’s band aged 18, Ike changed her name to Tina, and Ike and Tina Turner were born. The rest, like Chuck Berry’s story, is now well-documented history which you don’t need me to repeat.

Another music legend to start his career in St. Louis was the great bebop trumpeter, Miles Davies, who moved there as a baby with his family in 1927.

As the local website ‘Explore St. Louis’ says: “When the earliest forms of the blues migrated north from their birthplace in Mississippi Delta, they melded with the ragtime strains popular in St. Louis at the time and the result is what’s known as the St. Louis Blues.”

In a nutshell, then: St. Louis doesn’t just have the world’s best known blues tune named after it. St. Louis even has its very own blues genre.

Hi admin, i’ve been reading your website for some time and I really like coming back here.

Good stuff, Rachel. Thanks kindly for your feedback.