In my book ‘America’s Gift’, I quote the American Blues historian, David K. Bradford, writing about the nineteenth century African-American street evangelist, Charles Haffer. Born in the 1870s, Charles Haffer was a blind Delta balladeer and songwriter from Mississippi who astutely linked the emergence of blues to the guitar’s new popularity among black musicians in the 1890s. The guitar was the latest trend. There was nothing linking it with traditional black instruments like the banjo and violin, Haffer said. And nobody called what we know as blues music, ‘the blues’.

|

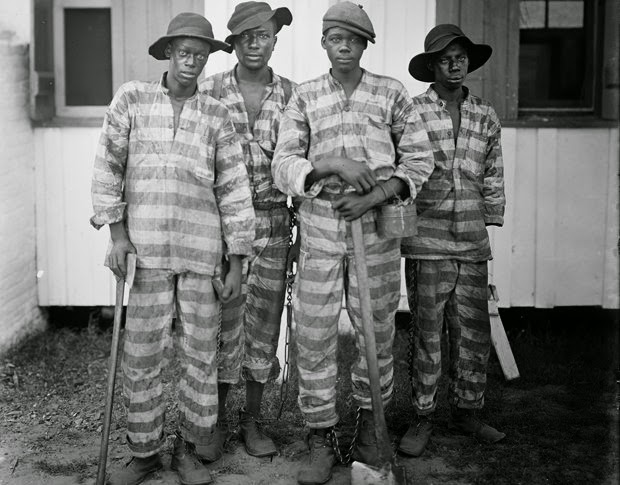

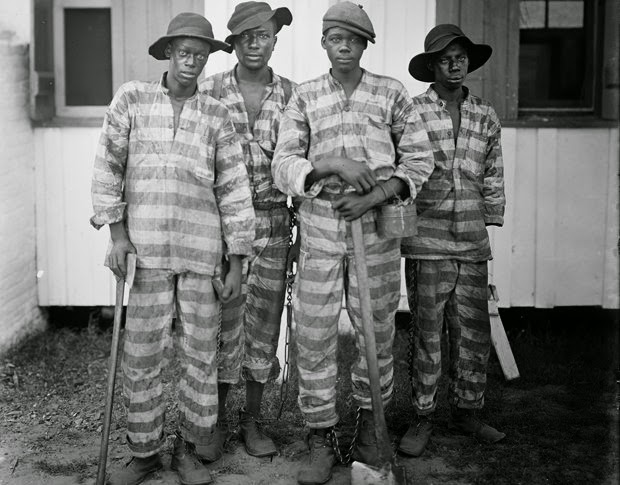

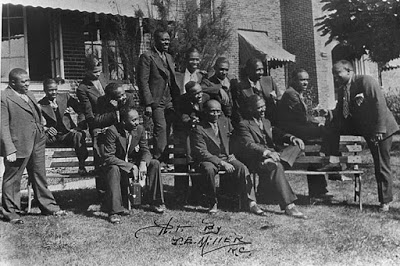

| Convicts c. 1910. Around 1895, Joe Turner trapped up to 80 convicts at a time, hiring them out illegally as work gangs, resulting in the subject of probably the earliest known blues. |

“I used to sing all the old jump-up songs”, Haffer said. “The blues weren’t in style then. We called them reels. The first blues I remember originated from a sheriff named Joe Turner. He was a kind-a bad man and if he goes after you, he’d bring you (in). His blues was very famous.”

I’ve been doing a bit of research on Joe Turner recently, in the search for that very first blues remembered by Charlie Haffer. It turns out that Joe Turner was an almost mythical figure in the black South, during the late nineteenth century, ands behaviour, both appalling and illegal, became the subject of what could well be the oldest blues song yet known. In 1915, the blues’ most iconic pioneer, W.C. Handy, wrote a song called ‘Joe Turner Blues’, based on an old folk song he said he’d first heard in 1895. This old song was certainly the same song Charles Haffer mentioned, about a ‘bad’ sheriff who transported convicts in chains. Handy, a great collector of rural black folk music, as many of you know, was the first person to call such music, ‘folk blues’. While Handy totally changed the lyrics for his Joe Turner Blues, the song’s structure was pretty close to the original.

(Handy’s Joe Turner, of course, had nothing to do with that great Kansas City blues shouter and early rock & roll pioneer, Big Joe Turner, who was only four-years-old when Handy wrote the song in 1915, while still based in Beale Street, Memphis.)W.C. Handy’s spoke about Joe Turner Blues in an interview he gave for a collection of ‘Negro Folk Rhymes’ by Scarborough and Gulledge in 1925, saying:

|

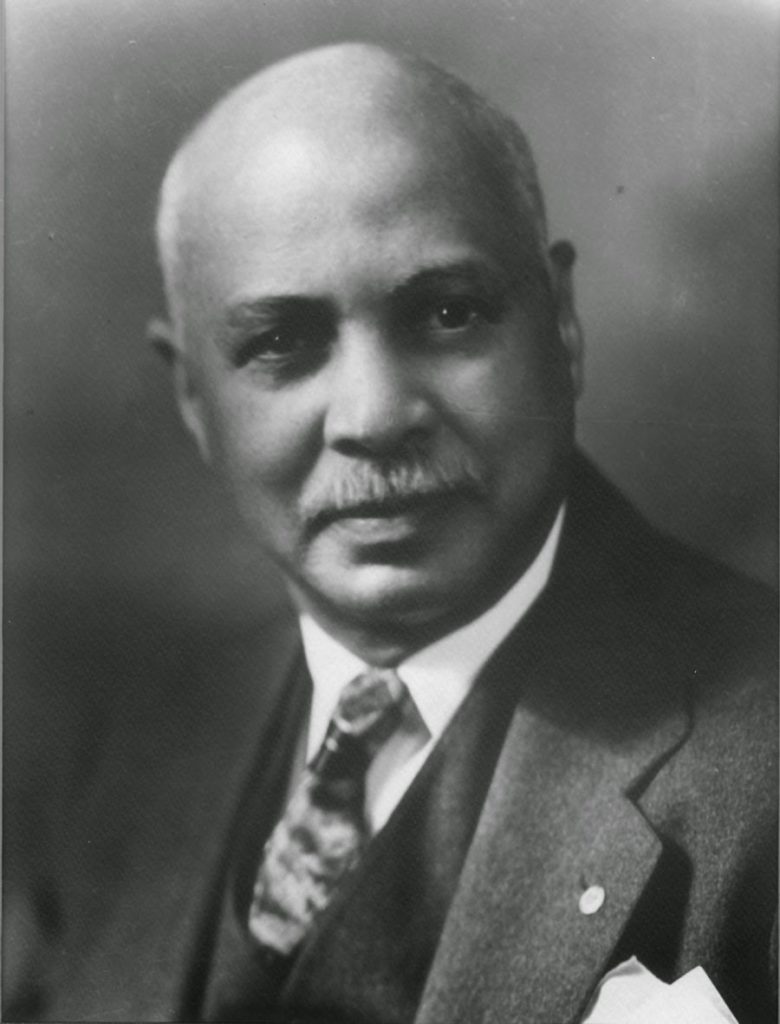

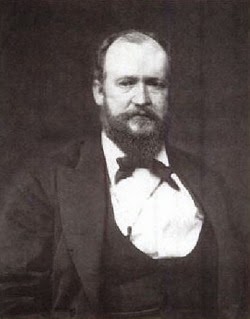

| W.C. Handy, the Father of the Blues, in 1892, aged about 20 |

“That is written around an old Negro song I used to hear and play thirty or more years ago (in 1895). In some sections (regions) it was called ‘Going Down The River for Long’, but in Tennessee it was always ‘Joe Turner’. Joe Turner, the inspiration of the song, was a brother of Pete Turner, once Governor of Tennessee. He (Joe) was an officer and he used to come to Nashville after a Kangaroo Court. When the Negroes said of anyone, ‘Joe Turner’s been to town’, they meant that the person in question had been carried off handcuffed, to be gone no telling how long.”

W.C. Handy expanded on the story of Joe Turner, in print, in his 1941 autobiography, ‘Father of the Blues’.

“Here you get folklore with a bang. It goes back to Joe Turney (also called Turner) brother of Pete Turney, one-time governor of Tennessee. Joe had the responsibility of taking Negro prisoners from Memphis to the penitentiary at Nashville. Sometimes he took them to the ‘farms’ along the Mississippi. Their crimes, when indeed there were any crimes, were usually very minor, the object of the arrests being to provide needed labor for spots along the river. As usual, the method was to set a stool-pigeon where he could start a game of craps. The bones would roll blissfully till the required number of laborers had been drawn into the circle. At that point the law would fall upon the poor devils, arrest as many as were needed for work, try them for gambling in a kangaroo court and then turn the culprits over to Joe Turney. That night, perhaps, there would be weeping and wailing among the dusky belles. If one of them chanced to ask a neighbor what had become of the sweet good man, she was likely to receive the pat reply, ‘They tell me Joe Turner’s come and gone’. Repeat this line three times and you get what I’ve called folk blues. Living in a world of such amazing cruelty, bewildered by the doings of such men as Joe Turney, this simple people either sang or played whatever came into their minds.”

“He come wid forty links of chain, Oh Lawdy!

Come wid forty links of chain, Oh Lawdy!

Got my man and gone.

Take a listen to this rare track: 1915’s Joe Turner Blues by W.C. Handy:

Handy’s autobiography continues: “Turney had a way of handcuffing eighty prisoners to forty links of chain, and from this situation grew many kinds of verses, all fitting the same musical mould. In Kentucky they call it, ‘Goin’ Down the River ‘Fore Long’. There it was a steamboat song, but for the tune it was Joe Turner right on. In Georgia you heard the same melody when they sang, ‘Goin’ Down That Long Lonesome Road’. You heard it all over the South, for that matter, but wherever it was sung the words dealt with a local situation.”

Dorothy Scarborough told Handy, in her 1925 interview with the famous blues pioneer, how she recalled a fragment of the original Joe Turner folk-song from the South, which she had never before understood. She quoted it to Handy.

“Dey tell me Joe Turner’s come to town.

He’s brought along one thousand links of chain;

He’s gwine to have one nigger for each link;

He’s gwine to have dis nigger for one link.”

|

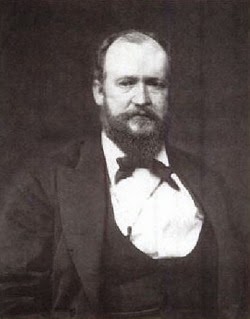

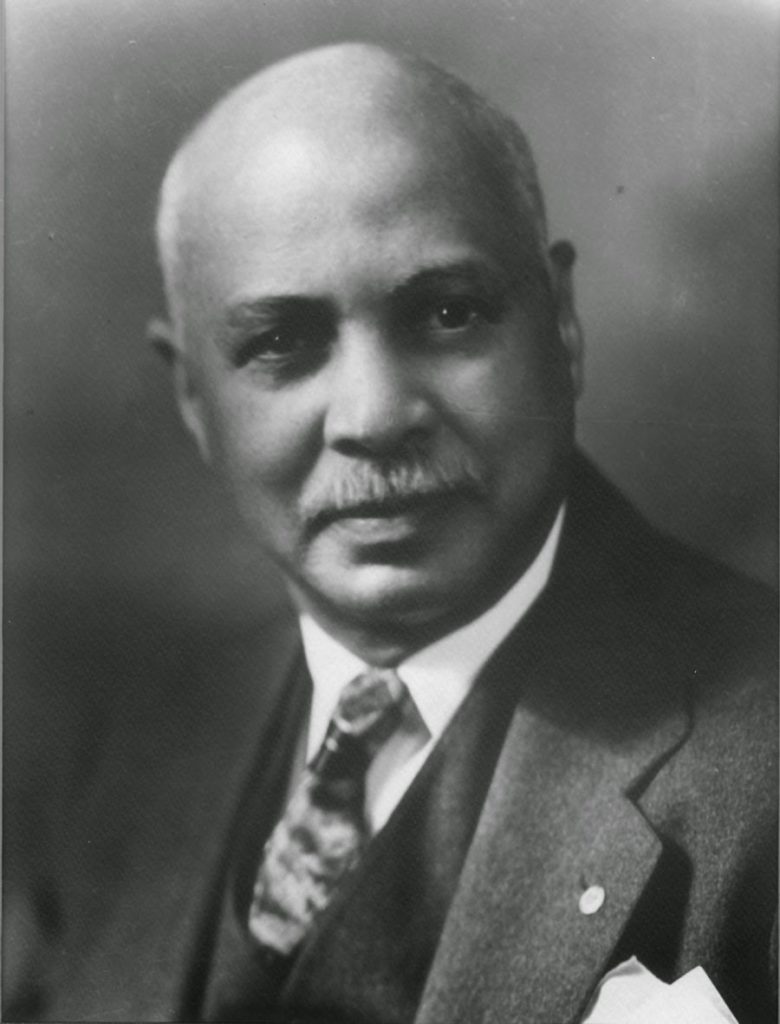

Civil War Confederate army officer and Tennessee

Governor, Pete Turney, brother of the dreaded Joe Turney (aka Joe Turner). |

Here’s another stanza from that earliest of blues songs found, amongst other vital clues, in a fascinating online discussion about Joe Turner conducted by America’s Mudcat Music Foundation in 1998.

“Dey tell me Joe Turner he done come,

Dey tell me Joe Turner he done come,

Got my man an’ gone.

Dey tell me Joe Turner he done come,

Dey tell me Joe Turner he done come,

Come with fohty links of chain.”

|

| W.C. Handy in later life |

While Joe Turney was known to have transported convicts in chains in to have transported convicts in chains in Tennessee,between 1892 and 1896, Mudcat also informed me about a stockade in Tennessee, built around 1891, called Joe Turney branch prison. Joe was the brother of Peter Turney, Governor of Tennessee from 1893 to 1897 and born in Jasper, Tennessee, in 1827. According to Wikipedia, Joe “used his political connections to run a chain gang for financial gain, inspiring a famous blues song ‘Joe Turner’.”

In her 1925 book, Dorothy Scarborough asked Handy why he moved the lyrical content in his own song so far away from the original Joe Turner concept. “Handy replied that in writing ‘Joe Turner Blues’ he did away with the prison theme and played up a love element, so that Joe Turner became, not the dreaded sheriff, but the absent lover. Here is the result, as Handy sent it out,” Dorothy Scarborough wrote in her 1925 book, “though folk-songsters over the South have doubtless wrought many changes to it since then.”

Here, then, are the lyrics to the blues sent out by W.C. Handy in 1915:

You’ll never miss the water till the well runs dry

Till your well runs dry.

You’ll never miss Joe Turner till he says good-bye.

Sweet Babe, I’m goin’ to leave you, and the time ain’t long,

The time ain’t long.

If you don’t believe I’m leaving’, count the days I’m gone.

Chorus

You will be sorry, be sorry from your heart (uhm),

Sorry to your heart (uhtn), Some day when you and I must part.

And every time you hear a whistle blow,

Hear a steamboat blow, You’ll hate the day you lost your Joe.

I bought a bulldog for to watch you while you sleep,

Guard you while you sleep; Spent all my money,

now you call Joe Turner ‘cheap’.

You never ‘predate the little things I do,

Not one thing I do. And tha’’s the very reason why I’m leaving you.

Sometimes I feel like somethin’ throwed away, Somethin’ throwed away.

And then I get my guitar, play the blues all day.

Now if your heart beat like mine, it’s not made of steel,

No, ‘t ain’t made of steel.

And when you learn I left you, this is how you’ll feel.”

Handy explained how he wrote his Joe Turney Blues. “Following my frequent custom of using a snatch of folk melody in one out of two or three strains of an otherwise original song, I wrote Joe Turner Blues and adapted the twelve bars of old Joe Turner as one of its themes. Here Joe Turner himself was no longer the long chain man; he was the masculine victim of unrequited love just as the singer in St. Louis Blues was the feminine, and he sang sadly and yet jauntily.”

Another probable reason, I believe, left unsaid by Handy, was that the negative portrayal of an evil white man, who made money by illegally trapping and hiring out black prisoners to convict farms along the Mississippi River, was too sordid a tale to appeal to the record-buying public in 1916. Highlighting the evils of the real Joe Turner would have been highly contentious in early twentieth century America.

Another blues icon, Big Bill Broonzy, in a filmed performance of his version of ‘Joe Turner Blues’ in 1951, spoke his introductory line thus, “This is a song that was sung back in 1892”. Big Bill wasn’t born until around 1893, so whether the song really was that old or Bill was simply picking a date out of his head, we’ll never know. We do know though, Big Bill did have a penchant for exaggeration.

Joe Turner Blues by Big Bill Bronzy circa 1951

|

| Big Bill was second only to W.C. Handy as an influence on modern blues |

In a 1957 interview, Big Bill said, “Joe Turner was a man that all the people in the South, they really believed in him. They really believed there was a man like that – and which it was. And nobody knowed who he was until he died. And the word Joe Turner, that was two people – because Joe was a Negro and Turner was a white man. And Turner was a man owned a big store there and people that got drought, caught in drought, got caught in storms and big floods and things – they’d lose their stuff. Why old man Turner would put Joe on a mule and put a sack of groceries or whatsoever he had and send it to these people’s houses. And they never did see nobody that bring it and they never did know who brought it – nuthin’. So they figured that that was the guy – that was all.”

Here then is the first part of Big Bill Broonzy’s Joe Turner Blues which, though portraying Turner in a benevolent light, picks up on the same chorus as used for folklore’s evil Joe Turner. The first verse is spoken.

“This is a song was sung back in 18 and 92

There was a terrible flood that year

People lost everything they had

Their crops, their livestock

This means their horses, their mules, cows

Goats and everything they had on their farm

And they would start cryin’ and singin’ this song

They tell me Joe Turner been here and gone

Lord, they tell me Joe Turner been here and gone

They tell me Joe Turner been here and gone

Then they would go out hunting rabbits, ‘coons and ‘possums

Anything they could catch

Sometimes they would catch something, then again, they didn’t

And when they would come home they would find

Flour, meat and molasses

In their homes and they would know that

Joe Turner had been there and left food for them

And then they would start cryin’ and singin’ this song

They tell me Joe Turner been here and gone

Lord, they tell me Joe Turner been here and gone

They tell me Joe Turner been here and gone, etc.”

For the life of me I can’t understand how the story of the bad Joe Turner is spun over to present the evil old bastard in such a humane light. Nevertheless, no other American folk song (folk blues as Handy would later describe it) known compares to Joe Turner Blues as a model for all the rural blues songs that followed.

Wrote one of America’s first blues authorities, the white music scholar and Wall Street lawyer, Abbe Niles, in 1926:

“Many verses in the folklore are in the blues spirit, yet are excluded from the blues form … (by) the singer’s own distinction. In this usage, it was only the verses that could be fitted to the (conventional) three-cornered (three-line) turns like Joe Turner (perhaps the archetypical blues song) that came to be called ‘blues’, and, conversely, they would say of a new melody to which they could not sing one of their three-line verses, ‘That ain’t no blues’.”

Niles was writing the introduction to 1926’s ‘W.C. Handy’s Blues, An Anthology: Complete Word and Music of 70 great (blues) songs and instrumentals.’ In other words, the musical capabilities of the blues player dictated whether a song was blues or not. Subsequently, in those earliest of days, the format of Joe Turner Blues served as the template upon which all pure blues (in the eyes of early blues snobs) was based.

“Super looking blog, will be back again and again. “Tony @tmulraney, Leinster, Ireland. 20 Feb 2015.

Hello Paul,

The usual rough dates given for when Pete Turney transported prisoners are old speculation based (for little good reason, when you think about it) on when his brother happened to be governor. I've found a newspaper article showing that he was already doing it in 1888. (Carroll County _Democrat_, Dec. 7, 1888.)

Handy also recalled "Got No More Home Than A Dog" as a "blues" he had heard in about 1895, and he made a guitar and vocal recording of it himself in 1938. (Handy pointed out more than once, because he was old enough to know, that no one was actually calling these kinds of songs "blues" songs back in about 1895 — consistent with the recollection of Haffer and others. Mentioning the word "blues" became popular in black folk songs in about 1907, about a whole 12 years after 12-bar tunes had become popular with black folk musicians. As a result, people began talking about "blues" music in about 1909.) Judging from various evidence, Mary Wheeler's book _Steamboatin' Days_ seems to center on songs of the 1890s (she deliberately sought out black singers much older than herself, and she was born in 1892), and although songs with two-line stanzas dominate the book, some are AAA or AAB, and some are notably similar to "Got No More Home Than A Dog."

It's been well established that Broonzy was born in 1903. We don't know whether Handy was the first person to use the expression "folk blues."

You wrote: "No other folk song currently known compares to Joe Turner Blues as a model for all the rural blues songs that followed." We don't know. We don't know how old the "Chilly Winds" and "Poor Boy Long Ways From Home" families of songs were, for instance. "Joe Turner" fits into the bad man ballad mold, it being about a bad man, whereas "Chilly" and "Poor" and "Got No" were very first-person-oriented, just as 1910s blues music was. In any case, there's no evidence anyone stuck the word "blues" into a variant of any of these songs until about 1906. For 1903 and earlier, we've got Charles Peabody, Anne Hobson, and the Thomas brothers combined (among others) giving us lots of black folk songs, some of which are 12-bar, e.g., and none of which have the word "blues" in them.

This folk song was collected by Howard Odum by 1908 and published by him as "Knife-Song":

"… 'Fo' long, honey, 'fo' long, honey,

'Fo' long, honey, 'fo' long, honey,

L-a-w-d, la-w-d, la-w-d!

… I hate to hear my honey call my name,

Call me so lonesome an' so sad.

L-a-w-d, l-a-w-d, l-a-w-d!

I got de blues an' can't be satisfied,

Brown-skin woman cause of it all.

L-a-w-d, l-a-w-d, l-a-w-d!

That woman will be the death o' me,

Some girl will be the death o' me.

L-a-w-d, l-a-w-d, l-a-w-d! …"

Odum also collected a song with related, AAAB lyrics by 1908:

"So she laid in jail back to de wall

So she laid in jail back to de wall

So she laid in jail back to de wall

Dis brown-skin man cause of it all."

On available evidence, mentioning having the "blues" in a black folk song in about 1907 may have had no particular association at the time with AAA, AAB, AAAB, or couplet and refrain.

Abbe Niles first heard a blues in 1913, and much of what he wrote about before 1913 would have been restating what his close friend Handy told him he recalled.

Supposing we say that anything that's apparently related to the 1910s blues songs and is 12-bar is a "blues," then we've got "The Bully" which is apparently from about 1892.

Hi Joseph. I’ve only just discovered your fascinating comment of March last year. I can only apologise for missing it. Unforgivable. Many thanks for your insight. It is much appreciated. I’m currently in the middle of a crossover between blog spot and word press so I’m in a bit of a blogging mess at the moment.

Thanks for your invaluable input, Joseph. Your knowledgeable comments are very much appreciated. (I've just deleted a previous version of this message because of a typo, by the way.) My apologies for such a late reply but I've only just stumbled upon your message. Unfortunately my 'Notify Me' box wasn't ticked so I wasn't, of course, notified about your comments.