The blooming of Bob Dylan

Blues guitarist Mike Bloomfield’s part in the blooming of Bob Dylan and how Bob went electric way before 1965.

To folk music fans of yesteryear, this is going to sound like sacrilege; so please excuse me. But I loved it when Bob Dylan went electric. It brought him out of that touchy-feely folky scene and into the tougher, more modern world of gritty rock & roll. I was reminded of Dylan’s electric re-birth when watching No Direction Home again the other night, Martin Scorsese’s 2005 documentary tracing Dylan’s life and his impact on world music and culture.

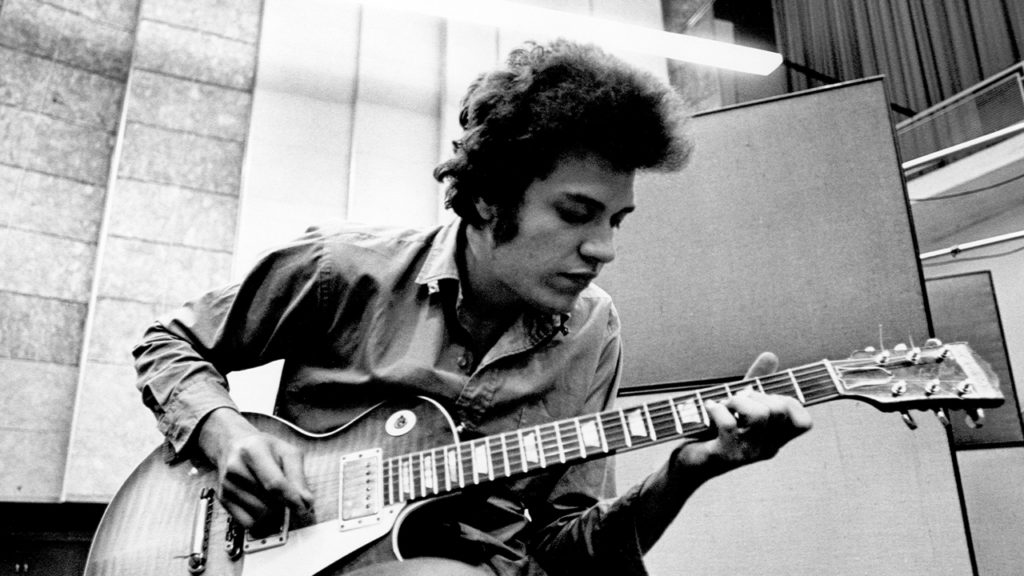

Scorsese’s Grammy-winning film reminded me of my days at CBS Records in London when Dylan was one of our principal artists. More importantly, it brought back memories of that fabulous American electric guitarist, Mike Bloomfield, whose biting, cutting blues-based soloing was instrumental, in my mind, in giving Dylan a creditable breakthrough into electric rock.

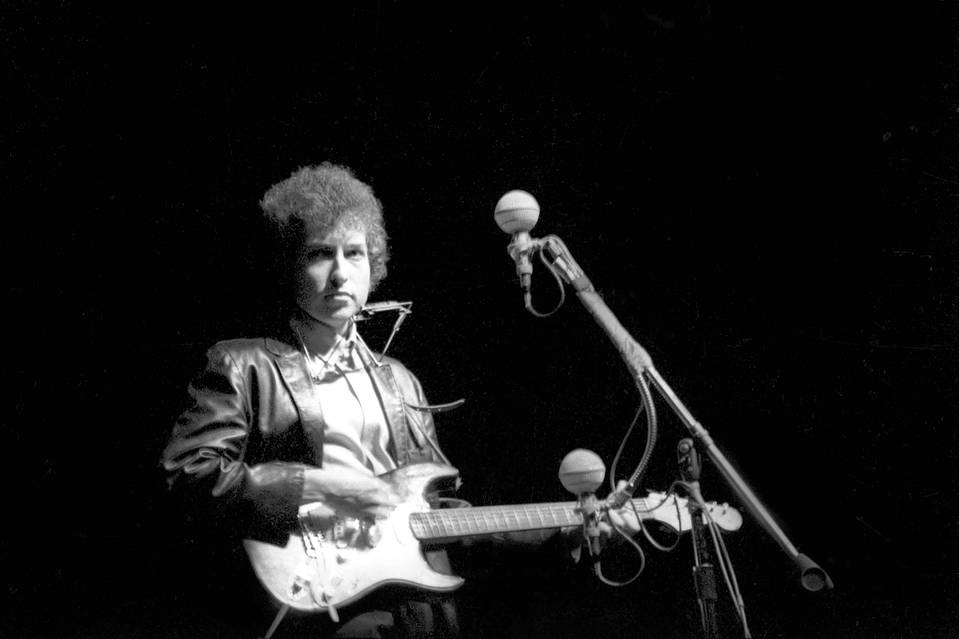

Oh, how they had booed, 50 years ago, when Dylan first went electric on stage, at Rhode Island’s Newport Folk Festival in 1965. The folk crowd simply couldn’t handle it, accusing Dylan of selling out. Pete Seeger, I believe, was in tears. Mike Bloomfield was on electric guitar that night, with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Dylan’s backing band at Newport. Al Kooper was on Hammond organ and, from what I’ve heard and seen, the band really cooked. The boos and catcalls started up half way through Maggie’s Farm. The link is below:

Mike Bloomfield backing Dylan at Newport 1965

Dylan’s first electric track in 1962

Aged just 16, the great George Barnes played pioneering electric blues guitar back in 1938 on some of the very first electric blues records by African Americans. These included Big Bill Bronzy, Memphis Slim and Memphis Minnie. George also pioneered 1960s American pop and rockabilly. He really was a master of most guitar genres instead of just blues.

When Bob Dylan brought his new electric sound to Britain the following year, he went down just as badly as at Newport. “Judas”, someone in the audience screamed, as the catcalls rained down. “Play it fucking loud”, Dylan told his new backing band, the Band. If Bloomfield had been playing, I’d probably have gone along, but Mike had rejected Bob’s offer to join him in favour of staying with Paul Butterfield’s band.

From Scorsese’s film, I saw that Al Kooper was hoping to play guitar on Highway 61 Revisited but was blown away, and knew he had no chance, when Mike Bloomfield started to produce his magic. Al did manage to bluff his way onto the session playing organ on Like A Rollin’ Stone. Although he was no virtuoso organist, Al’s improvised riff subsequently became a major part of the song’s appeal. On joining CBS, I discovered more Mike Bloomfield classics, like The Electric Flag’s 1967 album A Long Time Coming with Bloomfield on guitar, drummer Buddy Miles, organist Barry Goldberg and Nick Granites on vocals. A year later came the Super Session album featuring Bloomfield, Al Kooper and Steven Stills.

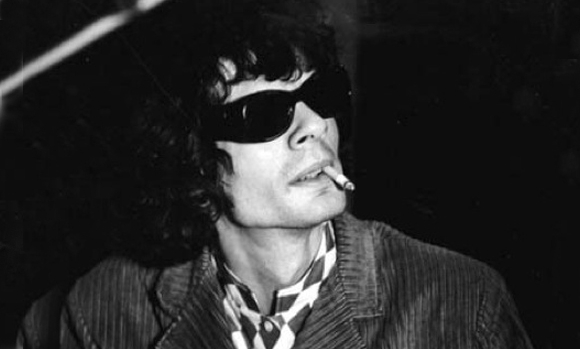

Unfortunately, I never met Mike Bloomfield, who died in 1981, but Al Kooper did spend an afternoon hanging around in our office in Theobald’s Road, Bloomsbury, for want of something better to do. This was around 1972. And it’s Al Kooper, of course, who has the more lasting legacy. Al formed Blood, Sweat and Tears in 1967, only to split a year later.Al mentored and cut the album Kooper Session in 1969 with the 15-year-old Shuggie Otis, who’s just won Comeback Artist of the Year at Living Blues magazine’s 2015 Awards. (Shuggie, son of R&B legend Johnny Otis, was also with CBS in 1969, with his Epic album, Here Comes Shuggie Otis.)

Once called the sane person’s Phil Spector, Al Kooper has played on and produced hundreds of seminal records. He played on the Rolling Stones’ Let It Bleed album including on the hit single, You Can’t Always Get What You Want, and has recorded with B. B. King, Cream, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Alice Cooper and The Who.

Kooper discovered Southern rockers Lynyrd Skynard in 1973, produced their first album and played on their first three. In 1969, Kooper made an album with Chuck Berry’s legendary piano player, Johnny Johnson. More recently, Al taught song-writing and record production at the Berklee College of Music, Boston, but has now retired.

In February, Al Kooper hits 72. We’ve lost the brilliant Mike Bloomfield, but like Dylan, Al’s a living treasure.

Regrettably, Kooper and Bloomfield appeared on the blues scene too late to make it into my untold history of the evolution of the blues, America’s Gift, but Bob Dylan does.

I saw Dylan play in Portland, Oregon with Barry McGuire opening for him. There were protestors outside because Bob had gone electric. It was my first concert. I don’t know how was in the band, but it got me hooked on music. My family moved to London in 1966 and I saw many concerts at a truly magical time in London up to the Stones concert in Hyde Park.

I was just listening to Paul Butterfield’s first album with Bloomfield, Elvin Jones and it still get my mojo workin’. Hard to believe it was recorded in 1964.

Barry McGuire, he’s the Eve of Destruction guy if my memory serves me right, Larry. “Wussies and pussies,” Dylan called the protestors and I totally agree with him. We shared much magic in London during those times, didn’t we.

Bloomfield with Dylan. I want to learn; and listen. Please send me whatever you can!

ASAP. David in New Zealand

That’s the only post I have on Bloomfield and Dylan, David, but since Dylan absorbed heaps of old blues, paulmerryblues.com should fill quite a few blanks for free. For the full picture, may I suggest you get America’s Gift, the untold story of how blues evolved, from Amazon at goo.gl/At5AZe