Iconic rock book, but no rock prophesy.

I’ve just re-read one of the seminal books on the evolution of rock & roll, 47 years after I first obtained it, so if that doesn’t date me, nothing will. Perhaps I was given it by the author. I simply can’t remember.

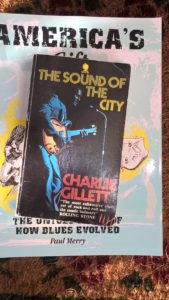

When I say ‘evolution’, I mean the history of rock music from the mid-twentieth century to 1970. The book, ‘The Sound of the City’ by Charlie Gillet, was once described by Rolling Stone magazine as “The most exhaustive study yet of rock and roll and the music industry”. It’s regarded as the first serious history of rock & roll and the most comprehensive. Even today, it’s still rated as one of the best; the best, according to the New York Times Book Review.

Charlie Gillett (1942 – 2010) was a Cambridge University-educated English rock writer, author and radio deejay, who followed up his Cambridge BA at New York City’s Columbia University in 1965. There he did his MA on the history of rock and roll music, something virtually unheard of at the time. Gillett turned his thesis into the book, first published in the USA in 1970.

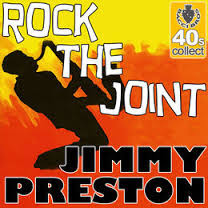

‘The Sound of the City’ traces the first 15 years of early rock ‘n’ roll, as the genre was termed then. (In the 70s, we started calling it rock and roll.) As the book says on its back cover, “It traces the sources of rock and roll, examining American regional contributions, and brings the history up to the present day (1970), including a section of the transatlantic echoes.”

When you read Charlie Gillett’s ‘The Sound of the City’ you’re reading how the rock music scene was viewed nearly 50 years ago by one of the most knowledgeable rock minds then on the planet. Indeed, rock & roll had only been a world force for 15 years. So, should you want a crash course in the music industry from 1955 to 1970, Gillett’s book is for you.

It’s an encyclopaedic font of knowledge that you might find a little old fashioned because of its age and terminology. But, as it was written at a time that I, too, worked in the music industry, it reassures me that terms like Dancehall Blues, Bar Blues, Club Blues, Country & Western, and so on, really were sub-genres back then, and I didn’t just imagine their existence.

I don’t agree with some of Gillett’s opinions; like the second paragraph in bold, below, for example, but here’s a sample.

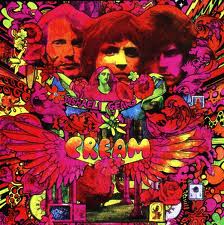

“By 1966, British hard style rhythm and blues had become more instrumentally versatile, progressing beyond the Chicago blues which had inspired the early Rolling Stones and set the style for much that followed. The leading musician was the guitarist Eric Clapton, who played successively with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, the Yardbirds and the Cream, playing hard blues in the style of B.B. King and Albert King but concerned much more than they were with technique and much less with emotional expression. Clapton’s influence was immense, both in Britain where where most guitarists and their audiences shared his concern for technical facility, and in the United States, where British groups, apparently regardless of their particular style, continued to appeal to audiences.

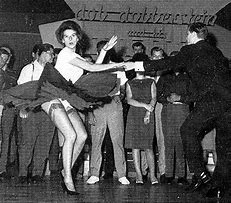

“But although the solos got faster and the singing became more ferocious, there was no longer any real emotion behind the music. In 1967-69, the Cream (prior to their break up), Hendrix, the American groups Blue Cheers, Steppenwolf, and others, had huge success in the singles and albums charts, but their anger was unreal, contrived to outwit an audience which had grown to identify noise with truth. The Rolling Stones played ‘Street Fighting Man’ like novices, creating much less excitement and political energy than the simple dance song theirs was modelled, Martha and the Vandellas’ ‘Dancing In The Streets’.”

Wow, that’s a bit harsh Charlie. I don’t think posterity will agree with you. But we have to remember that Led Zeppelin were in their infancy and Hendrix was still alive. Gillett wouldn’t have heard Clapton with Derek and the Dominos; and the Stones still had a fair bit of gas in the tank. Of course, it’s impossible to know what lies in the future and Gillet’s predictions proved more miss than hit, with his book’s final lines reading:

“Along with Sly Stone, Joe South, Tony Joe White, and Bob Dylan, John Fogerty – lead singer, guitarist, writer and producer of Creedence Clearwater Revival – seemed, at the beginning of 1970. To hold more promise for the future.”

Well, Dylan did get the Nobel Prize for Literature as we know. Charlie Gillett wouldn’t have seen that coming. As for Sly Stone, when I was promoting Sly’s ‘Family Affair’ single and album, ‘There’s a Riot Goin’ On, in the UK in 1971, we heard from Epic America that Sly was so coked up, he’d rather sit and watch ball games than go on stage. This unreliability was one of the reasons Sly & The Family Stone later disintegrated; and Sly’s music never again reached the lofty heights it achieved in 1971. He’d be 74 now.

Joe South won Grammys in 1969 for his single ‘Games People Play’ but after the suicide of his brother (who was also Joe’s drummer) in 1971, I believe he never released another single. Joe died in 2012, aged 72. I saw Tony Joe White on top of his game at the UK’s Hollywood Music Festival in 1970, rated as the best ever British music festival. For some reason, Tony Joe’s swamp rock didn’t kick on like we thought it would and he quit performing in 1980 to concentrate on songwriting. However, I’ve noticed lately that he’s making TV appearances again.

John Fogerty, too, never reach the heights Charlie Gillett predicted, though Fogerty did write ‘Rockin’ All Over the World’ in 1975, made world-famous two years later by the UK boogie band, Status Quo. Fogerty also reached number ten on America’s Billboard singles chart in 1985, with ‘Old Man Down The Road’. I believe Fogerty’s disputes with record companies had something to do with his lack of output for many, many years. He, too, would be 72 now.

Strangely, Charlie Gillett didn’t predict much hope for any British groups when talking about those bands who held promise for rock music’s future. The Beatles, he said, were no longer rock & roll with Lennon’s Plastic One Band being the more interesting group.

Heavy metal with Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple (no mention of the latter two in the book either) was about to launch but how could anyone predict that? However, Gillett was the first deejay to bring Dire Straights and Elvis Costello to public attention. He also discovered and managed Ian Dury and the Blockheads, produced American Lene Lovich’s worldwide new wave smash ‘Lucky Number’ and later, before his death in 2010, became heavily involved in world music.

I’m sure Charlie Gillet would be turning in his grave if he could see the state of music – let alone rock & roll – in 2017.