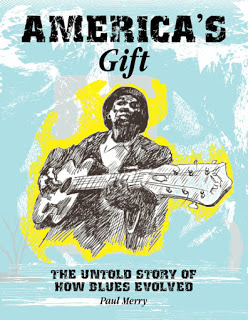

Why Lonnie Johnson was the most influential blues guitarist of all

“He (Lonnie) certainly had a presence: the blog points are well considered. Sadly, his grace and subtlety marginalized him.” @steviegurr May 19, 2015, California.

“Thank you, Paul. I enjoyed reading the writing on Lonnie Johnson you wrote. I agree he and Big Bill get overlooked.” bryanhimes @bryanhimes June 20, 2013.

While I can’t agree with the blues historians who say the first blues player ever recorded playing improvised guitar solos, note-by-note, on single strings, was Lonnie Johnson, I certainly think Lonnie was the most influential blues guitarist and singer there’s ever been.

Sylvester Weaver, incidentally, is generally considered to be the first to record what we now call lead guitar, in 1923, in New York. (See Sebastopol tuning post linked below).

https://paulmerryblues.com/2016/04/how-sebastopol-tuning-opened-the-door-to-open-blues-tuning.html

According to the eminent English blues historian, Paul Oliver, when Lonnie Johnson first saw Sylvester Weaver playing his acoustic guitar, behind blues singer Sara Martin in 1925, Lonnie was extremely impressed.

(And, apparently, Lonnie was very rarely knocked out by other guitarists’ work and rarely spoke about any other guitarist’s playing other than Sylvester Weaver’s.) I believe Lonnie himself told Paul Oliver this.

So let’s review why I think Lonnie’s influence is unmatched. Way back in 1927, Johnson pre-empted the modern guitar blues and rock solo on the then unreleased track, ‘6/88 Glide’, which you can now access on the net.

In recent years 6/88 Glide has received critical acclaim from jazz and blues scholars alike. An even earlier Lonnie Johnson track from 1926, ‘To Do This You Gotta Know How’, also features Lonnie playing and sustaining single notes.

All through the 1920s, Lonnie Johnson was considered the most influential guitarist of the era, alongside his recording partner, the Italian-American jazz and blues great, Eddie Lang. Because Lang was white, he recorded in the USA as Blind Willie Dunn, such was the controversy black and white artists making records together would have caused.

Johnson’s revolutionary playing throughout his career, it’s been said by many blues historians, strongly influenced delta bluesmen and urban Chicago blues guitarists alike, paving the way for today’s electric blues style. The blues icon, Robert Johnson, worshipped his namesake so much, said bluesman Johnny Shines, Robert would tell people that he was related to Lonnie Johnson.

Bob Dylan, too, wrote that he thought Robert Johnson learnt a lot from Lonnie Johnson and that some of Robert’s songs were new versions of Lonnie’s songs.

Another blues great, Brownie McGhee, once said Lonnie Johnson’s “musical works may and should be the first book of the blues bible.”

Lonnie’s influence was both in the cities and in the South

Walker stated that Lonnie and Scrapper Blackwell were far and away his favourite guitarists. And B. B. King says, ‘There’s only been a few guys that if I could play just like them I would. T-Bone Walker was one, Lonnie Johnson was another.”

In the 1930s, Johnson spent five years with Bluebird and Lester Melrose in Chicago, recording 34 blues tracks, including his race hits, ‘He’s A Jelly Roll Baker’, and ‘In Love Again’. For an example of Lonnie’s tasteful early electric guitar blues, check out, ‘She’s Only A Woman’ on YouTube, recorded in Chicago in 1939. The link is below.

Even after five years laying down blues with Lester Melrose (See The White Guy Who Gave Us Chicago Blues – May archive) during WW2, Lonnie Johnson wasn’t finished.

He had already taught the blues to George Barnes, the 16-year white electric guitar prodigy, who featured on many of Lester Melrose’s iconic pre-war Chicago blues recordings in the late 30s. (See BLUESMUSE19.)

As a measure of his versatility, Johnson had a number one hit in America as late as 1948, with his smooth crooning vocals and electric blues guitar fitting neatly into the West Coast Blues sound that would soon be called rhythm & blues. This was with ‘Tomorrow Night’, a track that spent

six weeks atop the American race charts in 1948, and was later covered by Elvis Presley. More R&B hits followed. Lonnie, probably through financial necessity, was now playing a style of music far removed from his earlier blues and jazz.

Why Lonnie’s not rated like he should be

You wonder if this sojourn into a softer, mellower style of rhythmic blues is one of the reasons Johnson is now so overlooked by the critics. As James Sallis wrote, “(Johnson’s) pop ballads, sentimentality and polish (professionalism) offended the seekers of ‘pure’ blues.”

In 1952, Lonnie Johnson was back playing blues in England, where his career had started in 1917. Even then, his continuing influence hadn’t finished. At London’s Festival Hall, in a famous name mix-up, Tony Donegan, a young British singer-guitarist opening for Lonnie

Johnson, was introduced as Lonnie Donegan. Another version his it that Donegan was so impressed by Lonnie, he took the American’s name as his own. Whatever the truth, the name stuck and Lonnie Donegan always said he was honoured and proud to have it.

Donegan, in turn, influenced a host of British rock bands from the Beatles and Queen, to the musicians who took blues back to white America like the Stones, Yardbirds, Fleetwood Mac and Led Zeppelin.

In 1970, in poor health after being hit by an out-of-control car, Lonnie Johnson made a live appearance in Toronto with another blues legend Buddy Guy. It was his final show and he died soon afterwards, in Canada aged about 76.

Paul Garon, a founding editor of the American magazine, ‘Living Blues’, complained bitterly of Lonnie’s relative obscurity in his magazine’s 1970 obituary for the blues great. Garon blamed the blues researchers who, “involved themselves exclusively with pre-war rural singers and post-war urban ones”.

Johnson was obviously too sophisticated for the first category and too ahead of his time for the second. As Garon said, “Lonnie did not fit any convenient category; he never had.”

Lonnie’s influence as a guitar player wasn’t even obvious at the time, with Elijah Wald, writing in ‘Escaping the Delta’, that Johnson was best known in the 1920s and 1930s as a sophisticated and urbane singer, rather than a musician. “Of the forty ads for his records that appeared in the Chicago Defender between 1926 and 1931, not one even mentioned that he played guitar.”

Take a listen to Lonnie Johnson playing more electric blues in 1966, below.