Great blues cities No. 2: New York.

“Thank you so much for … keeping the flame of the Blues alive with your Blog; it’s not often that true researchers of Blues dare to say the stuff you have written, for example, the ‘Grail’ of Congo Square article you wrote and also of New York being essential in the public’s early exposure to Blues. Please keep doing what you are doing; enlightening those who THINK they know about Blues.”

paul corry (@thebluesfreak), England, February 14, 2014.

Updated July 31 2019

In many respects, New York can lay claim to being America’s First City of the Blues and here’s why:

|

| Charles Matthews was singing black and black-inspired tunes in 1822. |

What happened next would change the course of music history. The company’s principal actor, a mixed-race West Indian called James Hewlett, was performing a soliloquy when the audience began shouting for ‘Possum up a Gum Tree’, one of the most popular Negro slave songs of the day. To Charles Matthews’ amazement, Hewlett abandoned his eloquent Shakespearean speech and performed the slave song on stage, singing in the required vernacular of the southern plantation, and dancing a slave-style jig. Charles Matthews, noting the wild applause Hewlett received, immediately incorporated Hewlett’s impromptu performance into his own stage act, the one touring the north-eastern USA.

|

| The man who inspired the blues. James Hewlett, above, inspired Charles Matthews to perform popular slave songs in New York in 1822. |

Charles Matthews’ impressions included the Fearless Frontiersman and the Clever Yankee, which American audiences loved incidentally. According to most observers, Matthews blacked up and tried to emulate the slave song as accurately as he could. He called the sketch, The African Tragedian.

Such was the success of Matthews’ American tour, when he returned to England, numerous imitators, white and black, sprang up in the United States performing the songs of the Southern plantations. These songsters began to describe themselves as ‘Ethiopian Delineators’, Ethiopian being the word to describe anything from Africa or black American, back in the early nineteenth century.

Ironically, one of the first entertainers to imitate Matthews’ act in America was James Hewlett himself, the actor Matthews had originally copied. Soon Ethiopean delineating was happening big-time in the U.S.

The most famous Ethiopian delineator of the era – of the nineteenth century even – also happened to be a New Yorker.

He was a white jobbing actor from Manhattan called Thomas Dartmouth Rice. Billed as Daddy Rice, even while just 20, Rice concocted the slave character Jim Crow whose songs and dances he performed in blackface both in America, and later in England.

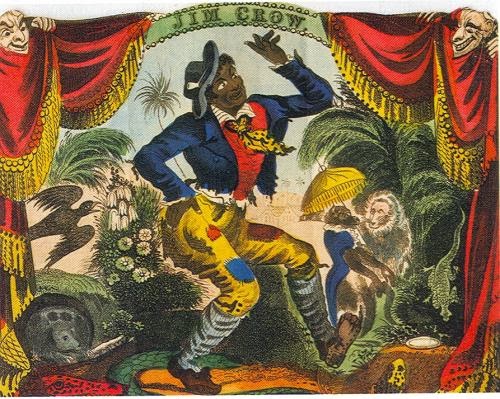

|

| New York’s Daddy Rice as Jim Crow in 1843. |

A poster (not the one above) in Eric Lott’s 1993 book, ‘Love and theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Working Class’, shows Rice dancing at the American Theatre in New York on 25 November 1833. Surrounding Rice is a throng of fans who have left the audience to join him on stage.

records of theatrical attraction”. Thomas Dartmouth Rice was the rock god of his era, so to speak, so successful that The Boston Post once exclaimed, “The two most popular characters in the world at present are Queen Victoria and Jim Crow”. Rice even started a dance craze that swept America called ‘Rocking de Heel’. Here’s a link to Jim Crow played by Tim Twiss on banjo. You can hear the syncopation.

|

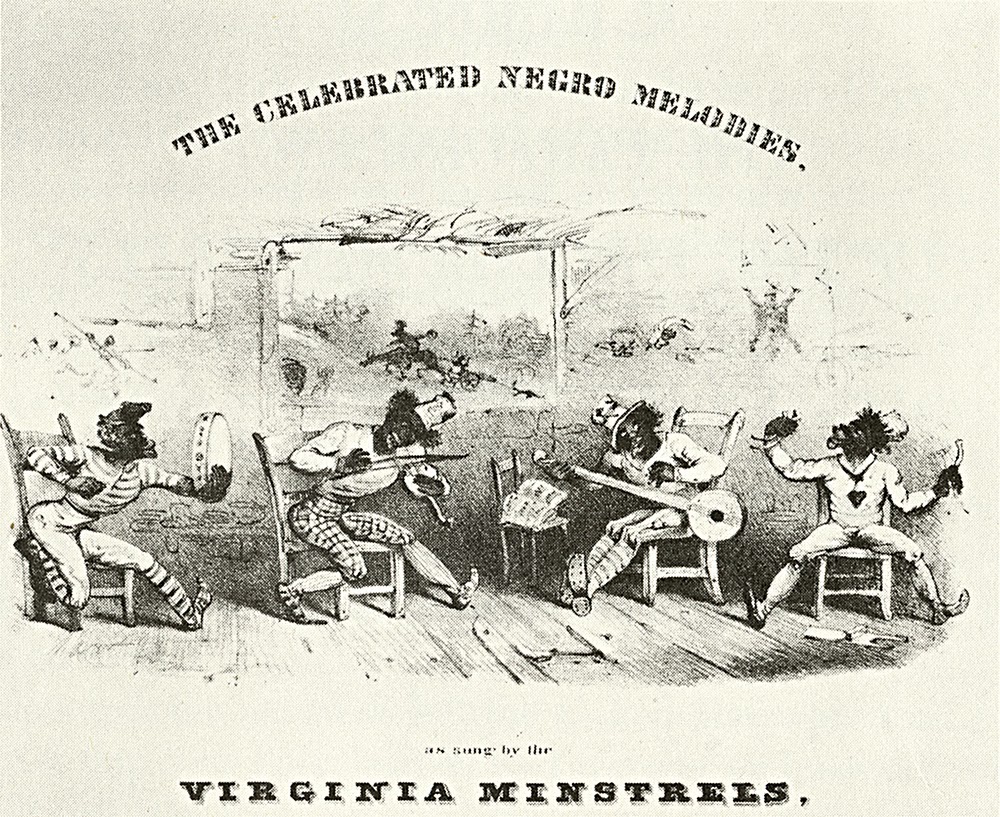

| The first minstrel troupe, for their sins, formed in New York City. |

All white men, they called themselves the Virginia Minstrels, a tongue-in-cheek response to the preponderance of yodelling Swiss and German alpine minstrel groups then touring the eastern seaboard. With names like the Tyrolese Minstrels, these European minstrels were constantly touring America during the 1830s and 1840s.

slave tunes and sang and danced in the manner of African Americans. The

audience loved it. Like Daddy Rice, the Virginia Minstrels were soon touring Britain and Ireland to packed houses.

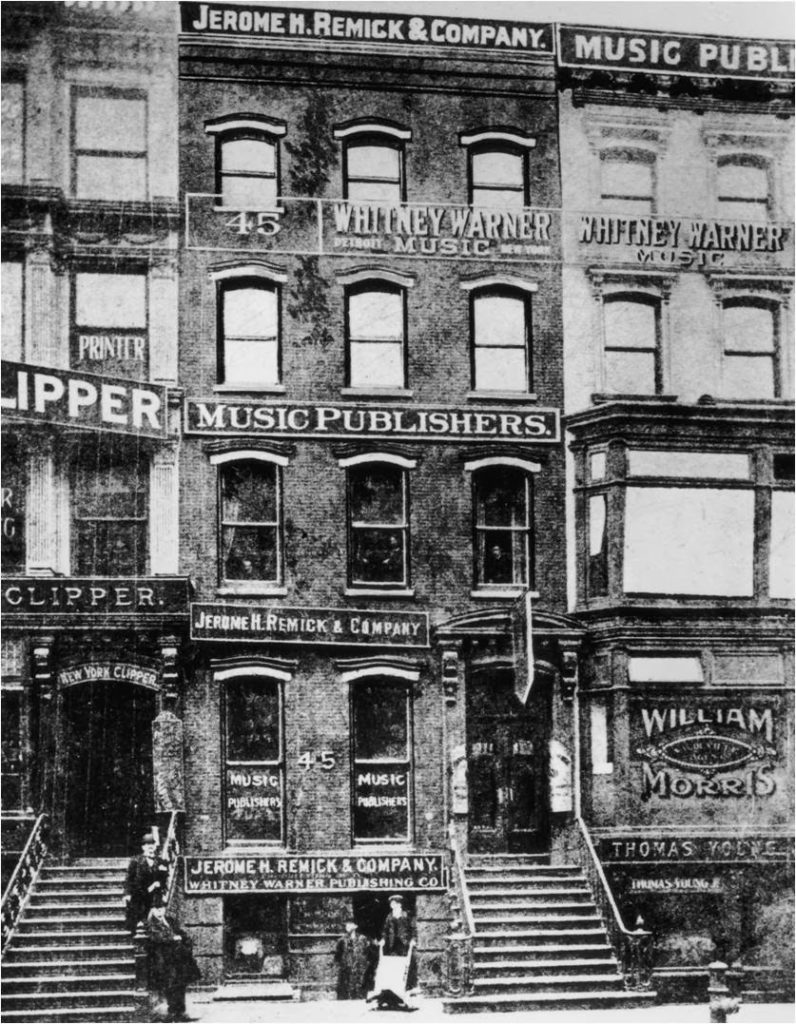

upsurge in published music. New York continued to be the centre of the world’s music publishing industry till at least the 1950s.

|

| Tin Pan Alley spread published blues like it spread the popularity of all home-grown American music. |

star and coon shouter who, at the time, was the highest paid entertainer in the United States. Born in Ontario, Canada, in 1862, May Irwin was one of America’s biggest and most controversial performers, earning a staggering $2,500 a week by the age of 25.

|

| May Irwin sang the blues New York-style in 1896. |

Listen to, Mr. Johnson, Turn me Loose, on You Tube. If you think it is blues,

you’ll agree it could well be the first published example of music including

blues nuances in existence. Back then, though, the song was simply described on ts sheet music as, “A coon novelty”.

Here’s the link to a recent performance by Bob Schulz:

|

| Morton Harvey. |

|

| Nora Bayes: first woman to record blues in 1916. |

Nora’s high contralto, while following a blues pattern, sounds hardly authentic today but, as Morton Harvey once suggested, the blues template hadn’t been laid down in those early years. Everybody was still finding their way.

Even in 1916, blues seems more of a white marketing term than the separate musical stream it would become in the 1920s.

While blues was recorded in London in 1917 by black new Yorkers and West Indians, it would be another four years before a black singer recorded a blues song in America. Even then, she had to be persuaded. If guitars were the instruments of the devil, as talked about in my previous post, then blues was the music of the devil. No self-respecting African American would bring themselves to record what they felt was the music of the lowest of the low. It would take the song-writing talent and blues field work of W. C. Handy to give blues a 12-bar template, structure and, most importantly, make blues respectable in the eyes of his fellow African Americans. And since Handy moved his publishing business to New York in 1917, most of the blues he worked on were written and compiled in New York. And New York is where W. C. Handy died, aged 84, in 1958.

|

||||

| Mamie Smith: the first black artist to record. |

In August 1920, Mamie Smith became the first black performer in America, male or female, to record a blues when she cut Crazy Blues in New York City. Mamie surprised herself and her record company by selling 75,000 copies, opening the floodgates for the stampede of black blues divas who followed her into the recording studio during the 1920s. Want to read more about how blues evolved? Here are two handy Amazon links to help you on your way.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Ddigital-text&field-keywords=how+blues+evolved+volume+one

http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Dstripbooks&field-keywords=how+blues+evolved

Thanks for this very interesting ‘Possum up a Gum Tree’ anecdote you dig up for us. One more to your credit !

The location, the African Groove Theatre on Thomas Street, made it occuring just a few blocks away from the place where Thomas Rice was raised on Bowery district. He was still a teenager in early 1820s. Then the time of this episode is probably the time when Rice was discovering the forerunner of hip hop battles, when Irish and Afro American young men were dancing for eels, every week, at the end of the Ste Catherine Market. He couldn’t all the more miss it that he was then an apprentice from a woodcarver working for the fishermen that supplied New York with fish on this market. Their cooperative stood right near the spot where this competition took place. Then, “Jump Jim Crow” was probably inspired by those figures they performed in front of an enthusiastic public. And it is likely Rice was also first impressed there by burned cork that white dancers used to paint their face with, in their attempt to imitate their black competitors. In his book, “Raising Cain. Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop”, W.T. Lhamon Jr. gives a broad description of those practices in the Bowery district during the early 19th.