Blues’ filthy forgotten ancestor

EXCLUSIVE. How blue American sea shanties led to filthy rugby songs and, unbelievably, blues.

|

| Two Rugby players say ‘hello’ before an evening of beer and communal sing song. |

I’m sure the reason that August 2013 post is so popular is because it features some of the filthiest blues and Rugby song lyrics ever written. If you ever wanted an example of the pulling-power of raunchy wordage, that post is it. Here’s the link, if you’re interested, but be warned if you’re prudish, it’s not pretty. But it is true.

https://paulmerryblues.com/2013/08/the-similarities-between-dirty-blues.html

When researching the link between the blues sung in the Delta and the songs bellowed out in Rugby Union club-houses around the world, I was astounded just how many Rugby songs originated in the United States. After all, the game was born at England’s elite Rugby School in 1823, supposedly when a 17-year old youth picked up a soccer ball and ran with it, crashing through his team mates. Ironically, this boy, William Webb Ellis, later became a church minister. He died in the South of France in 1872, a year after the Rugby Football Union was founded.

All the eagles, they fly high in Mobile,

All the eagles, they fly high in Mobile,

All the eagles they fly high,

and they shit right in your eye,

It’s a good job cows don’t fly, in Mobile.

(Chorus)

In Mobile, in Mobile,

In Mo, in Mo, in Mo, in Mobile

All the eagles they fly high,

and they shit right in your eye,

It’s a good job cows don’t fly, in Mobile.

There’s a Jew by the name of Cohen in Mobile,

There’s a Jew by the name of Cohen in Mobile,

There’s a Jew by the name of Cohen,

To the Christian Church he’s going,

‘Cos his foreskin won’t stop growing in Mobile.

(Chorus)

In Mobile, in Mobile,

In Mo, in Mo, in Mo, in Mobile

There a Jew by the name of Cohen,

To the Christian Church he’s going,

‘Cos his foreskin won’t stop growing in Mobile.

And so on and so forth. Apologies to any Jewish friends reading but, don’t shoot me, as they say, I’m only the messenger. I’m simply reporting lyrics that have existed way longer than the 113 years the U.S. Senate estimates blues has been around. And let me add, while no race, sex, creed or profession is safe from the irreverence of Rugby songs, they are never malicious, not even a verse about vicars buggering each other. I’ll include this and a few more verses from ‘In Mobile’ at the end of this piece, just so you can see what I mean.

Another thing that puzzled me when I started this research was just how many U.S. Rugby song web-sites exist, and how many American Rugby players feature on YouTube singing their blue Rugby songs. However, all has now become clear. Due to often identical lyrics, I’m now certain Rugby songs originated from sea shanties in the nineteenth century. So, too, did blues, and I’ll explain why further on. Another thing that surprised me (although it may not surprise Americans) is that sea shanties originated in the USA.

Sea shanties originated in America, not Britain

| In the 1840s, American shipwrights began building a new style of merchant ship, called the clipper. Designed to carry small but highly profitable cargoes, at high speed, over long distances, there’s evidence sea shanties developed on American clippers. |

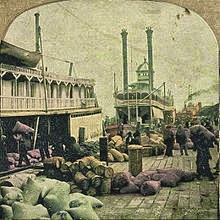

Sailors on American clippers sang in rhythm as they worked on board, using the same call and response techniques used by African-American slaves doing heavy lifting on the Southern plantations. Building on the traditional working chants of British, Scandinavian and French merchant sailors, American sea shanties were particularly influenced by the songs of African Americans loading cotton and tobacco in the ports of America’s south. One port in particular stood out: Mobile in Alabama.

A clue to the origins of sea shanties (and Rugby songs and blues) comes from an 1855 book, ‘The Merchant Vessel’, by the American journalist, Charles Nordoff. Born in Prussia in 1830, Nordoff wrote of seeing, as a teenager, work gangs in Alabama’s Mobile Bay, on the Gulf of Mexico. They used compressing jack-screws to force cotton bales into the holds of ships, singing as they worked. This would have been in the mid to late 1840s.

“Singing, or chanting as it is called, is an invariable accompaniment to working in cotton,” Knordoff wrote.

“And many of the screw-gangs have an endless collection of songs, rough and uncouth, both in words and melody, but answering well the purposes of making all pull together, and enlivening the heavy toil.

“The foreman is the chanty-man, who sings the song, the gang only joining in the chorus, which comes in at the end of every line, and at the end of which, again, comes the pull at the screw handles. The chants, as may be supposed, have more of rhyme than reason in them. The tunes are generally plaintive and monotonous, as are most of the capstan tunes of sailors, but resounding over the still waters of the Bay, they had a fine effect.”

The Mobile waterfront was famous as a major melting pot of sea shanties, where ships gathered and songs were exchanged. And just as American cotton went to Mobile for exporting, so American imports from overseas were loaded onto steamboats taking cargo from Mobile, inland into the American South, into such states as Alabama and Mississippi. Can’t you just see how the music provided by sea-shanties spread into what would later become blues country – the Delta?

Freed slaves (free black or free negro was a legal status back then) screwed cotton (amongst other things) for wages in Mobile in the 1830s and 1840s, and on America’s other southern docks, of course. They were joined at their work by black slave gangs rented out to the ports by their white owners, their ‘Masses’, to whoever organised and supplied the dock’s labour. No doubt the dock workers incorporated the ‘call and response’ make up of plantation work songs into their shanties and vice versa: the slaves taking sea shanties back to their plantations when their stints on the docks were over. Now, I bet you weren’t expecting this …

Whites loaded cotton with African Americans. They sang shanties, too.

Heavy exertion on the wharfs, and at sea, needed a rhythm to co-ordinate the movements of the teams of individuals providing the muscle. It’s understandable to assume these screw-gangs were always black. However, white sailors were also known to work as cotton-screwers on the docks, as early as the 1840s. As Charles Nordoff wrote in his book of 1855, these workers often came from Britain and Ireland, who wanted to avoid the viciously cold winters experienced out in the Atlantic Ocean.

Another nineteenth century white American author, Charles Erskine, wrote in his 1896 tome, ‘Twenty Years Before the Mast’, about his own laboring on the New Orleans docks in 1845:

“The day after our arrival the crew formed themselves into two gangs and obtained employment at screwing cotton by the day. With the aid of a set of jack-screws and a ditty, we would stow away huge bales of cotton, singing all the while. The song enlivened the gang and seemed to make the work much easier.”

Until these white merchant seamen took to partaking in sea shanties in 1840s America, the only people known to sing while they worked were Africans: either in Africa, or as slaves in the Americas. As early as 1806, the British women’s magazine, ‘La Belle Assemblée, observed how on the Caribbean island of Martinique:

“The negroes have a different air (tune) and words for every kind of labour; sometimes they sing, and their motions, even while cultivating the ground, keep time to the music.”

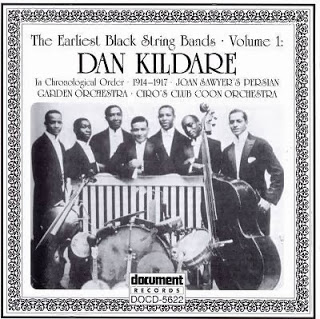

Parallels between black work songs, minstrel songs, sea shanties and, later, blues

Allen Isaac, writing in Ohio’s Oberlin College magazine in December 1858, described the similarity between African work songs and sea shanties.

“Along the African coast you will hear that dirge-like strain in all their songs, as at work or paddling their canoes to and from shore, they keep time to the music. On the southern plantations you will hear it also, and in the negro melodies everywhere, plaintive and melodious, sad and earnest. It seems like the dirge of national degradation, the wail of a race, stricken and crushed, familiar with tyranny, submission and unrequited labor. And here I cannot help noticing the similarity existing between the working chorus of the sailors and the dirge-like negro melody.”

The noted English sea-music historian, Stan Hugill (1906 – 1992), also drew parallels in his celebrated 1961 volume, ‘Shanties From Seven Seas’, between the songs of sailors and the American minstrel songs that started to emerge in the 1840s. The couplets in many minstrel songs were identical to those in shanties, he wrote, but which came first he couldn’t say. The ‘floating’ verses of minstrelsy and sea shanties were also heavily borrowed from each other, Hugill also observed.

It follows that blues borrowed from both, as well as traditional slave plantation forms, much later.

“It is perfect reading. I’m trying to download a kindle app so I can read your books.” Katie @BluesyKate, Kent, UK. 25 February 2015.

origin is certainly American. And crude as they are, you have to admit some are quite clever. (Rappers please note.)

had a breast,

Fantastic to see this history and derivation. We all sang these songs on my school outings but i never realised they came from Mobile Alabama. Wonderful history. Thanks.

Great to hear from you, Bill. Your feedback is much appreciated.

When reading James Lee Burke’s series of Dave Robicheaux novels that take place in Louisiana, I always wondered why the jailers and prison guards were referred to as “screws”. Now I know. Essentially they were forcing human cargo into tight spaces where the human cargo didn’t really want to fit.

Didn’t know that, CJ. Interesting fact.