When pianos thundered in Texas.

American Thunder: How rock ‘n’ roll evolved. Part One.

The first thunderous notes of the oldest of rock ‘n’ roll’s forerunners were hammered out by black musicians, on second-hand, often second-rate pianos called tin pans, in north-easternTexas, sometime around 1872. This new 1870s variety of popular piano music was just one of the musical strains that would later come together in the early twentieth century, being published and named as blues in 1912. Such piano music, in the 1920s, was given the name boogie woogie.

To position 1872 in the history of popular American culture, let’s remember that, barely a year earlier, the last of the great American cattle-drives had taken place. And, as we now know from census records, a quarter of those herding Texas livestock were African-American freedmen, some twenty percent were Mexican, a smaller number were native Americans, with the remaining fifty percent being either restless white men looking for adventure or former Civil War soldiers – from both sides.

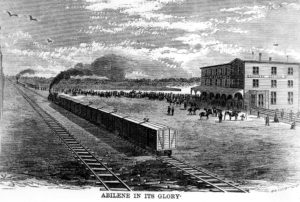

In 1871, about 5,000 of these tough-as-nails cowboys herded some 700,000 long-horn cattle, north from Texas to Kansas. Not in one go, naturally. It usually took one to two months, depending on the weather – which ranged from heat and dust to rain and wind. Cowboys from Texas delivered their cattle to places like Abilene, Kansas, which in 1871 was one of the wildest towns in the entire Wild West, or the fledgling Dodge City, where Wyatt Earp would make his mark five years later. Then, let loose with fists full of dollars, these cowboys went on wild benders in Abilene’s many brothels and saloons. Many would have encountered gambler and gun-fighter, Wild Bill Hickok, officially sworn in as Abilene’s sheriff in 1871, only to be sacked eight months later for accidentally killing his deputy in a shoot out.

As cowboys drank, fornicated, gambled and fought, in Kansas, the livestock they’d delivered was shipped from the state’s railheads and cattle-markets, by cattle-wagons pulled by smoking steam engines, to metropolitan slaughterhouses in population centres like Chicago. With 1871 standing out as the peak year for the Texan cattle drives, such mass bovine movement across America would never be seen again.

For cowboys of all races, work dried from 1872 onwards, just as the first sparks of the world’s most rocking piano music were beginning to ignite. To find out why, let’s paint a quick picture of what was happening in Texas in 1872.

With the American Civil War ending five years earlier, and slavery outlawed, new settlers were pouring into the Lone Star State. Confederate Texas had fought on the side of the South, of course, and many migrated to Texas from other defeated Southern states. Almost half of these incomers were recently-released slaves desperate for work and new beginnings. And who wasn’t looking for work and new surroundings, after the brutality, slaughter and destruction of America’s horrific internal war?

From the USA’s Northern states in the early 1870s, recent immigrants from Ireland, Sweden and Poland made their way to Texas, as well as free-born African Americans from north of the Mason-Dixon line. Out of Europe came new waves of Flemish, Dutch, Danish and Greek immigrants. With so many settlers being granted parcels of free land in Texas, new ranches, farms and land-holdings sprang up over the vast cattle corridors that once carved their way through the scrub and grasslands.

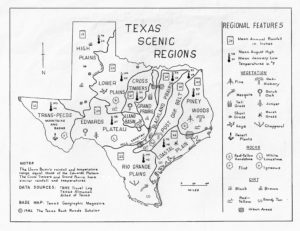

By 1872, then, as you’ll appreciate, wild cowboys driving massive herds of cattle through Texas was a huge inconvenience for the new land-owners. The last thing they wanted were thousands of cows shitting and trampling through their properties. Luckily, recently invented barbed-wire had just entered the market, which helped stop cattle in their tracks. As fate would have it, however, the need for cattle drives soon became redundant in Texas, due to the expansion of the railroad. From 1872, it became so much easier to move cows from Texas by steam train. So, from having a meagre 392 miles of rail track in 1861, the year the Civil War started, Texas had 1,578 miles in service by 1872. This four-fold increase was just the beginning, and the railroads soon became the most powerful industrial force in the state. Railroad companies were even accused of running Texas, politically, through bribery, hidden monopolies and corruption.

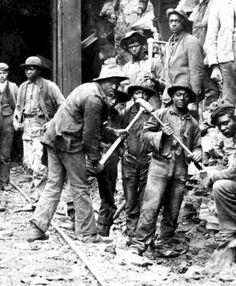

In spite of this, the railroad – not just in Texas but throughout the United States – became the biggest employer of black workers in American history. Explained Ted Kornweibel, Professor Emeritus of African-American History at San Diego State University, in a 2010 interview with KPBS public radio: “The entire southern railroad network that was built during the slavery era was built almost exclusively by slaves. Some of the railroads owned slaves, other railroads hired or rented slaves from slave owners. And the most shocking thing that I found was that women as well as men were actually involved in the hard, dangerous, brutal work of railroad construction and (women) continued to work for railroads (in lesser roles) after they were built.”

Unusually for those days, said Professor Kornweibel, hired slaves, free blacks and white workers worked on the railroad side-by-side. “Both black, free blacks, as well as white workers. There were some categories of work in which both slaves and free persons worked, like brakemen, like firemen stoking the firebox on a steam locomotive. Other jobs like maintaining the track were almost exclusively the province of black workers. And what’s significant here is that the pattern set during slavery, what blacks were allowed to do or not allowed to do, that then became the national pattern after the Civil War. More blacks were railroaders than were steel workers, coalminers, loggers, than (worked in) any other industry. And for Southern blacks, especially (to get a job on the railroad), it was low pay but to get a steady job, a steady income – There’s a blues that says:

The railroads – in the South – were the best alternative (for African Americans) to escaping two worse fates, either agriculture which often meant sharecropping, which meant you were in debt year after year after year, or domestic service.”

The workers, then, clearing the way and laying down rail tracks through Texas, during the early 1870s, were clearly African Americans, both former slaves from the South and economic migrants from the North. I wouldn’t be surprised to find redundant black cowboys amongst them, either. In one place in particular, the presence of these workers instigated those first magical notes of rock & roll. Their uninhibited, exciting piano music igniting in the great pine, oak and hickory forests of North eastern Texas.

North of Houston, east of the prairies and lakes linking the cities Dallas and Waco, these forests are unambiguously called Piney Woods. At 54,400 square miles, Piney Woods covers an area almost half the size of England, stretching into Louisiana, Arkansas and even Oklahoma. And as you know, where woodland existed in the nineteenth century, logging camps and sawmills surely followed. Follow they did. Slowly taking advantage of new routes carved through the dense forest by freshly-laid railroad tracks came the timber harvesting companies. Before the Piney Woods lumber boom in the 1880s, these forests were so uninhabited, they were historically the refuge of escaped slaves, outlaws and other fugitives. With no established settlements, employees laying railroad track or working lumber in Piney Woods were put up in woodland camps. To stop the men becoming too bored with life in such isolated areas, most work camp operators provided entertainment halls for drinking and relaxing after work, often supplying those rickety old upright pianos, known as tin pans, for music and even dancing. And brothels. More about that next time.

Fascinating!! Can’t wait to continue reading!

Great stuff, Trish. Many thanks for your feedback.