When blues guitarists were counted on one hand.

Black guitar owners – rare as gelding balls before 1890s.

If you read my last post, you’ll know I featured Henry Sloan, the African-American farmer in Mississippi who taught Charlie Patton how to play early Delta Blues guitar around the turn of the 20th century. But where did Henry Sloan Henry – born in 1870, just five years after the end of the American Civil War – get his musical influences?

As discovered when researching my blues history book, America’s Gift, there are no references to narrative work songs, as sung by African-American slaves, at any time before the Civil War concluded.

This strongly suggests the blues song, as we know it today, only originated after the American Civil War was over in 1865. Backing this up is research by U.S. music academic, Dr David Evans, claiming the first musician to set field hollers to guitar accompaniment was our afore-mentioned Henry Sloan.

So, rather than being influenced by earlier Delta Blues musicians, Henry seems to have been the starting point: the influencer of all the other Delta Blues performers who followed; even though it is his pupil, Charlie Patton, who is today hailed as the King of the Delta Blues Guitar.

It’s worth noting that Henry Sloan’s father, Samuel, moved to Mississippi from America’s Piedmont region, today famous for its finger-picking guitar style, known as Piedmont-style or East Coast Blues. Samuel Sloan, born in 1842 in South Carolina, moved to the Mississippi Delta aged around 20. The only report I can find, ‘Ghost of Henry Sloan: Unravelling the Mystery of Henry Sloan’, says Samuel Sloan was a farm worker, but I can’t substantiate this. But it could well be true as South Carolina, in 1862, had a comparatively large free black population of 9,914 people, one third of whom lived in Charleston. Out of two choices, then, one possibility is Samuel Sloan migrated to Mississippi looking for work. The other is Sam was taken there as a slave?

For the record, between 1820 and 1860, more than 60 per cent of the Upper South’s slaves were ‘Sold South’. Walking 25 to 30 miles a day, men, women, and children were marched south in large groups called coffles. Slave traders bound the women together with rope, handcuffing the men in pairs to the chains around their necks.

Whether Samuel Sloan was free man or slave, though, is a moot point. When Sam’s son, Henry Sloan, was born five years after the Civil War, the North’s victory had ensured the Sloan family, as with all African Americans, could rightfully live as free human beings.

All we can do today is speculate upon how Henry Sloan came to pick up the guitar, because it simply wasn’t a common instrument for the working classes in those days. Black people, especially black men, playing guitars before 1890 in America were as rare as hens’ teeth, as people said back then. The guitar, before 1890, was mainly a well-to-do white woman’s instrument and I know of only a handful of black men known to have played the instrument before then. The main reason was this: before the mail order industry came into being around 1895, guitars were bloody expensive. This means Henry Sloan must have had the means to buy or borrow one. The U.S. Census of 1900 lists Henry as a farmer so, hopefully, he earned enough to enable him to buy a guitar.

That Henry Sloan was musical, there’s no doubt. But did he teach himself the guitar and, if so, who did he learn from? Was his father, Samuel Sloan, musical too? If so, did he ever teach his son, Henry, the East Coast Blues? Is that where Delta Blues started? We can never know. And please consider that many of the Delta Blues runs and phrases were copied from the great Lonnie Johnson, the New Orleans-born guitarist many experts rate as the most influential blues guitarist ever and the second biggest seller of blues records during the 1920s after Blind Lemon Jefferson.

Here are the other African-American blues guitarists known to have been around before 1900:

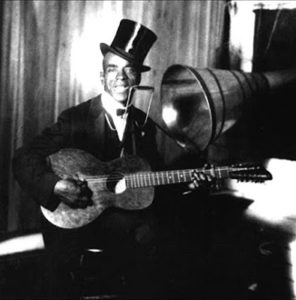

Daddy Stovepipe, born Alabama, 1867.

One of the earliest-born black, male,19th century guitarists we know of was Daddy Stovepipe, a man who hailed from Mobile, Alabama. As a major cotton port, Mobile is where the sea shanty of the 1840s – a uniquely American innovation – reached its zenith. Taking their cue from the earlier Ethiopian delineator songs, and interacting with the fledgling minstrel songs, American and African sailors and dockers – black and white alike – sang sea shanties. The Civil War took these shanties to both Union and Confederate areas of America, where I’m convinced they played a major part in the evolution of blues. Here’s a link to one of my earlier posts examining this theory, which I believe is unique.

http://https://paulmerryblues.com/2015/02/dirty-blues-lyrics-and-filthy-rugby.html

Daddy Stovepipe was known to have played in a mariachi band down in Mexico in the late 1890s. He could well be the earliest-known blues guitarist, if only we could

authenticate the music he was playing in the USA before heading south to Mexico. But, of course, even the most bluesiest music back then wouldn’t have been called blues. Such music would only be officially named in 1912.

Daddy’s real name was Johnny Watson but he also recorded as Jimmy Watson, Sunny Jim and the Reverend Alfred Pitts. Johnny Watson was called Daddy Stovepipe due to his ever-present stovepipe hat, as you can see in the pic above.

Daddy Stovepipe was the fourth male rural blues artist to record solo, in 1924, when he was a mature 57-year-old. Stovepipe was yet another black entertainer to have performed with the famous Rabbit Foot Minstrels, whose tours played a major role in taking the blues to the South. Other well known members of the ‘Foots’, as they were known, included Brownie McGhee, Ma Rainey and Rufus Thomas.

Daddy Stovepipe cut ‘Sundown Blues’ in Richmond, Indiana, on 10 May 1924. All references to Sundown Blues maintain Stovepipe sang, played guitar and harmonica. Some say it was the first blues harp recorded. However, the harp on Daddy’s Sundown Blues sounds to me more like quills (comparable to panpipes) or even a flute. Indeed, Stovepipe’s ‘harmonica’ reminds me of the flute melody on Canned Heat’s ‘Going up the Country’ from 1968, a melody, in turn, based on a quills tune by Texas bluesman Henry Thomas, recorded in 1928. All this aside, even if Stovepipe was playing a harmonica, it wasn’t quite the first blues harmonica captured on disc. But that will have to be the subject of another post; or check it out in America’s Gift.

According to The Blues Trail website, the Gennett label’s mobile field unit recorded Daddy Stovepipe in 1927 in Birmingham, Alabama, along with an unknown character called Whistlin’ Pete. Daddy Stovepipe then appears in Chicago in 1931, recorded by another mobile unit, belonging to the American Record Corporation. This time Daddy was recorded playing with his wife, Mississippi Sarah. Says The Blues Trail:

“She (Sarah) was a good singer and an expert jug player, and the couple’s humorous back-and-forth banter make the (eight) sides they made together a very special side attraction in recorded blues.”

After Sarah Watson died, Stovepipe toured America’s Southwest and Mexico, The Blues Trail site adds, before playing in Zydeco bands in Louisiana and Texas during the 1940s. Amazingly, Daddy Stovepipe’s last recording was made in 1960, at the grand old age of 93.

Charlie Galloway, born 1863, and Jefferson Mumford, born 1873 – both in New Orleans.

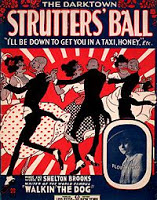

Charlie Galloway, born in New Orleans in 1863, is the earliest-born African-American guitarist I’ve found. His New Orleans compatriot, Jefferson Mumford, came along ten years later, in 1873. Both men were barbers, like so many of the pioneer blues musicians, and both were known to be playing on the streets of New Orleans as far back as 1885. Both guitarists, therefore, were there at the height of the coon song era, when those offensive songs, along with minstrel songs, evolved into ragtime. And both were at the top of their game when ragtime, in turn, morphed into blues around 1895, influenced by the legendary New Orleans horn player, Buddy Bolden. Indeed, both Galloway and Mumford had stints playing in Buddy Bolden’s seminal band – probably the first known blues band of them all.

As mentioned, African-American guitarists were highly unusual in the 1880s and 1890s. Not only were guitars expensive, but only gut guitar strings were available in that era. They, too, like the gut strings on a violin, were prohibitively expensive.

As mentioned, African-American guitarists were highly unusual in the 1880s and 1890s. Not only were guitars expensive, but only gut guitar strings were available in that era. They, too, like the gut strings on a violin, were prohibitively expensive.

Indeed gut guitar strings might cost as much as a worker’s entire weekly disposable income. You’d have to be doubly-keen and doubly-wealthy to afford and maintain a guitar before 1895.

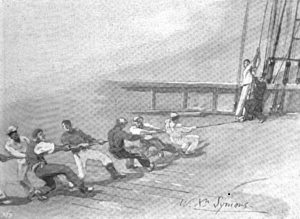

That’s Jefferson Mumford holding his guitar with the Buddy Bolden band in the pic above, although I’m pretty sure the negative here is transposed, as I believe Mumford was right handed. The guy with the cornet, or trumpet, is Buddy Bolden, who went insane, probably due to drugs and alcohol, during a New Orleans street parade in 1907. Aged 29, Buddy Bolden would spend the rest of his life in an asylum, dying in 1931, unheralded and unrecorded.

Fabulous stuff Paul…all of it..I’m a recording artist / troubadour and heavily influenced by the power of the Delta..I hang out in Clarksdale home to my mentor and teacher Son House..Dick Waterman introduced me to him whilst busking in London 1970 .

I have your book…love the matter of fact detail…hugely entertaining.

Just wanted to say Hi n thanks….thought you might be interested …despite existing under the radar as a blues loving slide playing singing songwriter I have earned praises from Knopfler , Clapton..Andy Lowe..Albert King Joe Boyd blah blah.

Working on my 15 th album now…Kind regards keep up the good work as they say x

Great to hear from you Kevin. You’ve some top guitarists who’ve sung your praises including Albert King, the guy who turned me onto electric blues around 1964. Would you be the KB who left a review on Amazon Books? If so, many thanks. It would be nice to do a post on you at paulmerryblues.com where I can tie it in with your Amazon comment. Many thanks for your great feedback.