Great blues cities No. 5: Memphis.

|

| Handy’s Memphis Orchestra in 1918. Handy is third from right, back row |

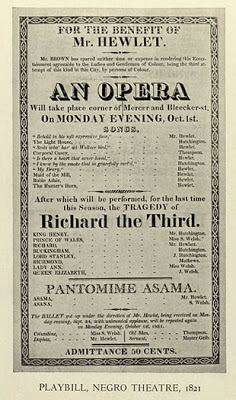

Just

as the first blues ever published (in 1912) was titled, “Dallas Blues”, so the

first blues ever recorded (in 1914) was, “The Memphis Blues.”

which was written and published in Oklahoma City, The Memphis Blues was

actually written in Memphis and published in Memphis to boot. Its composer was

Alabama’s W.C. Handy who had moved his band to Memphis in 1909 to play the

clubs on downtown Beale Avenue, as the street was called then. Black musicians

had been playing on Beale Avenue since the 1860s, with one of the first

ensembles based there being called the Young Men’s Brass Band. Brass band

music, a craze that started in Newcastle Upon Tyne, England, in 1809, moved to

America in the 1830s, where it remained highly popular until around 1920. This

might explain why most of the first blues records were by brass bands or

orchestras.

|

| Memphis Minnie |

wonderful Memphis Minnie moved from Louisiana to just south of Memphis at the

age of seven, and ran away to busk on Beale Street in 1910. Minnie was just 13.

Born Lizzie Douglas, Memphis Minnie got by playing and singing the blues while

working as a prostitute. Apparently, this wasn’t uncommon for female blues

singers in an era with no social security. Minnie was such a top blues

guitarist she’s said to have outgunned Big Bill Broonzy in a guitar duel in

Chicago in 1933, where she also helped introduce country blues. Minnie’s

‘When The Levee Breaks’, written in 1929, was reworked by Led Zeppelin on Led

Zeppelin 1V in 1971. Here’s a link to Minnie on a 1953 track called ‘Kissing in the Dark’ all

about sexually transmitted diseases:

|

| Beale Avenue became Beale Street after this |

Memphis performer from that era, who is now largely forgotten, is Miss Floyd

Fisher, also known as the Doll of Memphis, who toured as far north as New York

City and Chicago, in a double vaudeville act with Baby Seals. You may remember

Baby Seals as the composer of the first published blues with vocals, as

featured in my post of 11 June 2013. His song, ‘Baby Seals’ Blues’ was

published in August 1912, as performed by Baby Seals and Baby Fisher, as the

Doll of Memphis had now become. A description of Miss Fisher appeared in the

African-American newspaper, The Indianapolis Freeman, in 1910: Baby Floyd

Fisher “is the smallest and sweetest little thing on the stage, singing

anything the audience asks. In that way, she holds the house as long as she

wants to.” Apparently, Miss Fisher could do everything from singing and dancing

to male impersonations and cracking up the audience.

a tune to promote a man standing for Mayor of Memphis. His name was Edward “Boss”

Crump and the jingle obviously worked as Crump was duly elected. In 1912, two

songs with a similar structure to Handy’s advertising jingle were published as

blues. This must have stung Handy into action because he then renamed his ‘Mr

Crump’ tune as ‘The Memphis Blues’ and published it. This was the third and

last of the three blues published that first year of the blues: 1912.

pinpoint 1912 as the year ragtime as a genre morphed into blues. While Handy’s original Memphis

Blues sheet

music was subtitled ‘That Southern Rag’, there was no mention

of rags

|

| Alberta Hunter |

on the record packaging when the song was released as the first blues

record in 1914.

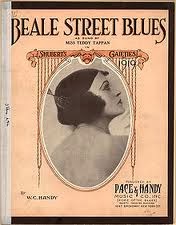

a blues trail by writing blues songs in Memphis until 1917, when he moved to

New York. Landmark Handy compositions, written in Memphis, included ‘St. Louis

Blues’, the song that introduced blues to the world, first published in London

in 1916. From London, ‘St. Louis Blues’ spread around the then British Empire, to

places like Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa and even back to

America. Jazz, at this stage, was still at its embryonic stage, still called

jass, and was a music Handy had little time for. While some people think Handy

invented jazz, he was a 100 per cent blues man and apparently didn’t care much

for jazz at all. In 1916, Handy wrote ‘Beale Street Blues’ which he published

in 1917, inspiring the Memphis authorities to change the name of Beale Avenue

to Beale Street.

Memphis-born blues singer Alberta Hunter (1895 – 1984) co-wrote and recorded the acclaimed, ‘Down Hearted

Blues’, for the black-owned record label Black Swan in 1922. Now aged 27, Alberta

had already performed in Paris and London, back in 1917, so was certainly no Memphis

ingénue.

1923, Bessie Smith made her recording debut covering Alberta’s ‘Down Hearted Blues’,

quickly becoming one of the biggest African-American blues stars of the era,

popular with blacks and whites alike. Many older readers will remember Alberta

Hunter from the 1970s when she came out of retirement aged 83 and sang the

blues classic “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down And Out” on television. But, before

you follow the link to Alberta, here’s one to a mind-blowing version of that

song by Derek & The Dominos recorded in 1970. To me, you just won’t hear

better.

Albert Hunter’s version is a little more sedate than Eric and Bobby’s etc. but

follow this link and you’ll witness a live performance by one of Memphis’s

greatest blues singers. I think the year she was filmed was 1975.

performers between the

|

| Franks Stokes, right, and his childhood friend, Dan Sane |

1920s and 1940s. Such musicians helped create the style

now known as Memphis Blues. Frank Stokes, born just outside

Memphis in 1888, is still considered by many as the Father of Memphis Blues

Guitar. In 1927, aged 39, Frank got together in Memphis with Dan Sane, 31, to

record as the Beale Street Sheiks. The fluid interplay between Stokes and Sane,

their propulsive beat, witty lyrics and Stokes’ stentorian voice make their

recordings irresistible, says a local Memphis guide book. Here’s a link to the

Beale Street Sheiks recorded in 1927.

|

| Rev. Robert Wilkins (1896-1987). Rediscovered in the 1960s. |

Wilkins, a guitarist of African-American and Cherokee descent (like so many

early bluesmen), who could be heard playing blues and gospel on Memphis radio

in 1927. Born 21 miles outside Memphis, Wilkins claimed to have tutored the

great female blues guitarist, Memphis Minnie, and also worked alongside a W.C.

Handy protégé, Walter ‘Furry’ Lewis, also from Memphis.

Lewis (1893 – 1981) is worth mentioning because he spectacularly opened for the

Rolling Stones, aged 81, on American TV’s The Tonight Show Starring Johnny

Carson, in 1974.

Memphis was also a great city for jug bands, including Will Shade’s Memphis Jug

Band, which often included Memphis Minnie on vocals and guitar. They played

slow blues, hokum (humorous, raunchy blues), pop and dance tunes. While the

first jug bands came from Louisville, Kentucky, the Memphis Jug Band made over

80 recordings between 1927 and 1934, making them America’s most recorded

pre-WW2 jug band. Another popular Beale Street jug band, and there were many,

was Gus

|

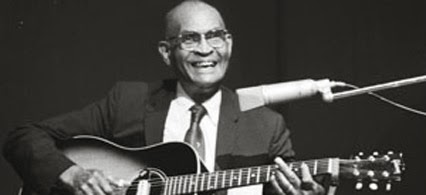

| The smokin’ blues of Albert King |

Cannon’s Jug Stompers who recorded ‘Walk Right In’ in the 1930s, a song

more recently made famous by Dr. Hook (or Dr. Hook and the Medicine Show as I

remember them in 1972, when I helped promote ‘Sylvia’s Mother’.

blues legends who played on Beale Street between 1920 and 1940 included Louis

Armstrong, and Rufus Thomas who moved to Memphis at the age of two. Then there was Memphis Slim (born John Chapman in

Memphis, in 1915) who moved to Chicago in 1939 where he became Big Bill

Broonzy’s piano player. Chapman was given the nickname ‘Memphis Slim’ by Lester

Melrose in 1941 when recording ‘Grinder Man Blues’ and other songs; but used

his father’s name, Peter Chapman, for many of his compositions. These include

‘Every Day I Have The Blues’, recorded by Ray Charles, Eric Clapton, Jimi

Hendrix and a host of other blues and jazz luminaries.

World War Two, when thousands of African American musicians were forced from

the Mississippi Delta by poverty, many made their home in Memphis, changing the

old classic Memphis Blues Sound to a sound more familiar today. These musicians

included the velvet bulldozer, drummer and magical blues guitarist, Albert King;

Howlin’ Wolf; Ike Turner and

King, originally billed as the ‘Beale Street Blues Boy’.

|

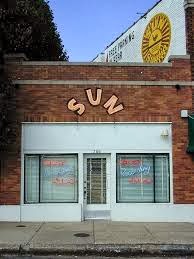

| Memphis’ most famous building? |

|

| Not the first rock & roll record |

gained the attention of the world after Sam Phillips opened his Sun Studios in

the city in 1950, recording then amateur bluesmen like B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf

and Junior Parker. He also recorded a 19-year old Ike Turner performing ‘Rocket

88’ as Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats, released in 1951, often wrongly

described as the first rock & roll record. Ever the publicist, I suspect it

was Sam Phillips himself who started that rumour. You only have to check my

archives and read the post of 8 August 2013 ‘Ten Rock & Roll Records (of

the 1930s and 40s) That Pre-empted Rock & Roll’ to see how hollow a claim

that was.

|

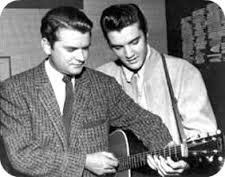

| Sam Phillips and his protege |

was Phillips recording of black bluesmen who put Memphis in the world spotlight

of course. It was his idea to get a white boy who sounded like a black bluesman

to make a record in Memphis in 1954. That white boy, as we all know, was Elvis

Presley, and the world was never the same again.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Ddigital-text&field-keywords=how+blues+evolved+volume+one