First blues families: the Chatmons.

Is Bolton, Mississippi, the true birthplace of the blues?

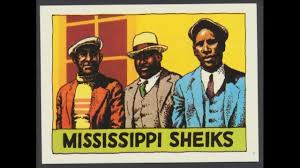

Anyone who knows the Mississippi Sheiks knows, at their core, were three sons of the nineteenth century ‘musicianer’, Henderson Chatmon, a one-time slave from Terry, Mississippi, noted for his brilliant violin playing at plantation square dances.

Henderson, born around 1850, also ran a string band, the late nineteenth and early twentieth century’s version of a rock group. String bands were all the rage at dances and gatherings throughout the United States, playing everything from waltzes and square-dances to ragtime.

A short digression.

For instance, down in New Orleans, sometime around 1895, guitarist Charlie Galloway decided to put a cornet player in his string band. The hot ragtime they produced became what we now call gutbucket blues. The cornet player, Buddy Bolden, then left Galloway in 1896 to form his own string band, one with a fat brass section. Buddy’s trumpet, or cornet, would play lead over the rhythm guitar, drums and other instruments, improvising over the top. The rest, as they say, is history, but the music they played wouldn’t be named blues until 1912. This unique style of new Orleans music later forked away from hot blues to become Dixieland jazz or, in the UK, trad jazz. But I digress …

At the same time, Henderson Chatmon was living in Bolton, Mississippi, a tiny town not far from the state’s capital, Jackson. Henderson’s wife, Eliza, would play guitar in their string band; and when their kids got older, they would help out on guitar, banjo, double bass, mandolin and harmonica, amongst other instruments. The Chatmons had nine sons and two daughters, altogether, all of whom inherited their parents’ musical ability.

So which strand of the music leading to blues was first, Bolton’s or New Orleans’? Both are contenders really, but there were many other strands in the mix, from all over the place. For the full lowdown, you’ll have to check my book, America’s Gift at http://goo.gl/At5AZe

Back to Bolton.

But back to Bolton, Mississippi. Also living and farming there was one of the earliest blues guitar players I know of, a mysterious delta blues guitarist called Henry Sloan. Whether Henry taught the Chatmon boys, we don’t know. But we do know he taught a young Charlie Patton, now hailed as the father of the Delta blues guitar. Take a listen to Patton’s famous ‘Pony Blues’ below.

Around 1905, The Patton and Chatmon families, together with Henry Sloan, all moved 100 miles north to the Dockery Plantation, today often highlighted as birthplace of the blues. It certainly has a claim, if you don’t count Bolton, since many blues greats worked there including Sloan, Patton, Eddie ‘Son’ House, Pop Staples and, taught by Patton, Howling’ Wolf. Indeed, Robert Johnson was given his first guitar there in 1930.

So, how much did Henry Sloan influence Charlie Patton? (Many people use the spelling ‘Charley’ but Patton, himself, preferred ‘Charlie’ so I’ll go with what Charlie wanted.)

Son House and Tommy Johnson (from the nearby Webb Jennings Plantation) who often accompanied Charlie Patton, once said Charlie Patton dogged every step of Henry Sloan. Indeed, Tommy Johnson even claimed famous Charlie Pattons songs like Pony Blues, above, were originally Henry Sloan compositions.

Was Henderson Chatmon Charlie Patton’s father?

Young Charlie Patton jammed often with Henderson Chatmon’s musical sons in the early twentieth century, so much so, a rumour persists, to this day, that Henderson Chatmon was Charlie Patton’s father. However, Charlie’s mother and his surviving relatives always denied this. Charlie’s religious father, like many African Americans of the era, believed music to be of the devil. The young Charlie Patton, it appears, spend time at the Chatmons’ place, simply to play music out of range of his old man.

So who were Henderson Chatmon’s sons? The most famous is probably Armenter Chatmon, better known as Bo Carter (1893 – 1964) who made his recording debut in 1928 aged 35. Armenter Chatmon both managed and played in the Mississippi Sheiks, one of the best-known African-American country blues groups of the 1930s, as well as enjoying a noted solo career.

Sitting On Top of the World.

Mainly a guitar and fiddle band, the Sheiks first big success was in 1930, with the now iconic blues standard, ‘Sitting On Top Of The World’, written by Armenter’s brother, violinist Lonnie Chatmon (1888 – 1943), and guitarist and vocalist Walter Vinson (1901 – 1975). Walter Vinson, too, hailed from Bolton, Ms.

As well as Armenter Chatmon (aka Bo Carter), a third brother, guitarist and harmonica player, Vivien ‘Sam’ Chatmon (1897 -1983) completed the Mississippi Sheiks. Sam, I’ve read, often used to claim Charlie Patton was his half-brother, apparently to take advantage of the later Charlie Patton craze. So did Sam start the rumour? Probably.

Like all blues performers back then, including Robert Johnson, the Mississippi Sheiks played waltzes, reels, Tin Pan Alley pop songs, ballads, coon songs and minstrel show tunes, as well as blues and hokum blues, to cater to both their white and black audiences. Muddy Waters, who played in a similar string band when young, said he “walked ten miles to hear them play.”

Is there an older blues family than the Chatmons? Stay tuned to find out.

“Tommy Johnson even claimed famous Charlie Pattons songs like Pony Blues, above, were originally Henry Sloan compositions.” Hi Paul, is you source for this J.F. Derry, because I asked him for a source and he didn’t come up with one.

I think I came across that quote in a number of sources, including Dr. David Evans who got it from Charlie’s niece. However in America’s Gift I do say the following:

“As we’ve heard, Tommy Johnson claimed famous Charlie Patton songs, like ‘Pony Blues’, were originally Henry Sloan compositions. As Tommy Johnson was the only person to make such a claim, do we take it face value? Perhaps he was an alcoholic just mouthing off and it was the Canned Heat talking. Perhaps, even, Tommy Johnson was jealous of Patton’s success, since Tommy never recorded again after 1929, being under the mistaken impression that he’d signed away his right to record. (He was probably too drunk to know what had happened.) We’ll never know why Tommy made such a claim.”