Birth of the Blues/Rock Guitar hero.

Updated: September 14, 2021.

Electric blues and rock guitar heroes … do they still exist, or are they relics of the past, now most possible note combinations and innovations have long been worked out?

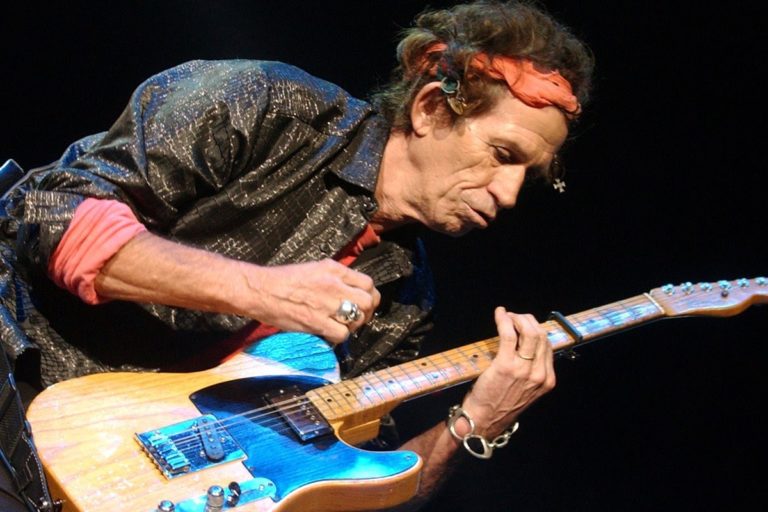

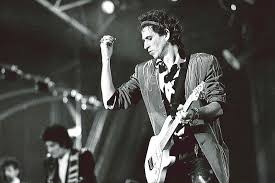

That’s not a question I feel I’m qualified to comment on, subjectivity being the main influence on who your top rock and blues guitarist is. However, it did please me to read Keith Richards finished 2016 voted number four on musicradar’s (the top website for musicians, it claims) 23 best rock guitarists in the world right now.

Number 1 was Blink-182’s Matt Skiba who I checked out on video. An accomplished rock/pop guitarist, certainly, there’s no way in the world, in my opinion, he matches the rock/blues guitarists of yester-year. Working roughly backwards in time (the memory’s not what it was), for world class blues rock guitarists of innovation and influence as I remember them coming through, I’d rate the following 30 axemen:

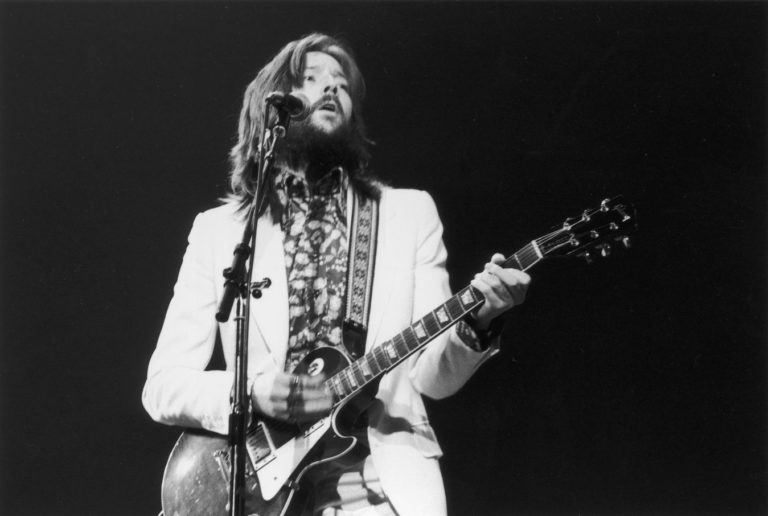

Joe Satriani, Slash, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Joe Perry, Eddie Van Helen, Angus Young, Brian May, Joe Walsh, Mick Taylor, Duane Allman, Johnny Winter, Tony Iommi, Jimmy Page, Peter Green, Jeff Beck, David Gilmour, John McLaughlin, Carlos Santana, Eric Clapton, Mick Green, Chuck Berry, Buddy Guy, Albert, B.B. and Freddie King, Scotty Moore, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and T-Bone Walker.

I’ve chosen a clip here of John McLaughlin because he’s so low-key these days, it’s possible some won’t have heard him. I had the pleasure of knowing John during his time at CBS in London and have seen, first hand, what an amazing guitarist he is – one of the few who play a double-necked guitar because they truly need to. He started off playing blues rock with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce in bands like the Graham Bond Organisation before crossing over to jazz to play with Miles Davis. Jeff Beck (who was also on our label at the time) has called John McLaughlin the best guitarist alive. Below, John’s playing with Gary Husband (keys); Etienne Mbappe (bass) and Ranjit Barot (drums) on a recent track they called ‘Lockdown Blues’.

As I said, the list of names above is not in order of preference, but going back through my memory. But who influenced such exceptional players as these? Before even the brilliant T-Bone Walker in the 1940s, we had electric guitar innovators like Texan Eddie Durham, of African-American, Irish, Mohawk and Cherokee descent. Durham was the first electric guitarist commercially recorded, on his own home-built amp in 1929, with ‘Everyday Blues (Yo-Yo Blues)’, for Benny Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra.

Ironically, many sources credit Eddie Durham with making the first electric guitar recording of all time on a track actually recorded some six years later. This subsequent 1935 cut, ‘Hittin’ the Bottle’, was a Swing-era record with Eddie’s blues-style guitar licks, for another African-American bandleader, Jimmy Lunceford.

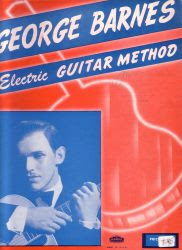

Following Eddie Durham was the white blues guitar prodigy, George Barnes – a ‘wonderkind’, the Germans call such talent in one so young. In English, and in George’s case, this can literally be translated into ‘wonder kid’. On March 1st 1938, George Barnes was in the unusual situation of playing electric guitar on different versions of the same two blues tracks, ‘It’s a Low-Down Dirty Shame’ and ‘Sweetheart Land’.

One session was for the legendary Big Bill Broonzy, the other for blues pianist, Curtis Jones. George Barnes was the only white face amongst the stellar blues artists being produced in Chicago by Lester Melrose. George’s fluid electric guitar licks backed Big Bill, Blind John Davis and other black blues luminaries such as Washboard Sam, Jazz Gillum, Louis Powell, Merlene Johnson, Hattie Bolten and possibly Memphis Minnie.

Altogether, young George Barnes played on 33 seminal African-American blues recordings in Chicago in 1938. While George was almost certainly the second guitarist to record electric blues commercially after Eddie Durham, some sources mistakenly claim George Barnes to be the first recorded electric guitarist of them all. While he wasn’t quite that pioneering, I can safely maintain that George Barnes literally wrote the book on playing the electric guitar. Still in his early 20s, in the early 1940s, George wrote the world’s very first instruction books teaching people how to play the electric guitar. The George Barnes Legacy Collection website sums up his place in history, saying how George was:

“Before Charlie Christian, who adored and lauded him. Before Les Paul, who admired and envied him.”

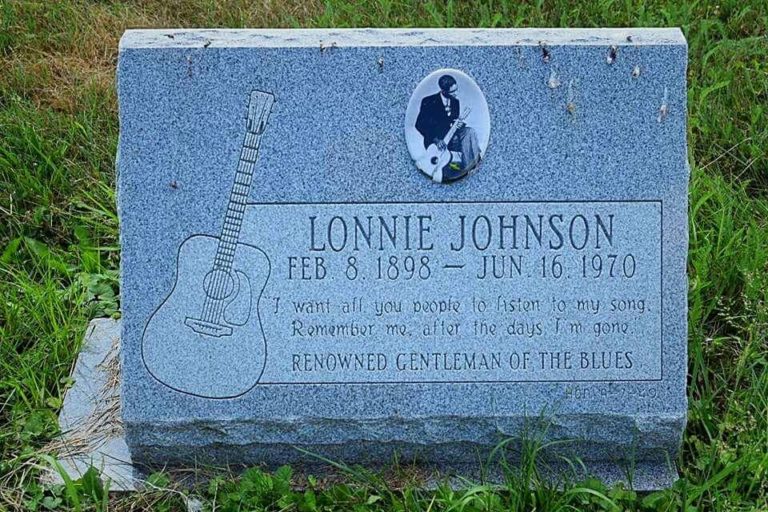

In an interview found on Dave Gould’s Guitar Pages, George Barnes described how he was taught by the African-American blues guitar maestro, Lonnie Johnson.

“When I was young I hung around with Lonnie Johnson, and he taught me how to play the blues. He played the first 12-string guitar I ever heard. He used to tune it down a whole tone to make it easier to play … In 1935, I started recording with the top black blues artists of that time. (That would make George 14 when he started recording blues guitar, presumably acoustic blues guitar).

“I made over 100 blues records with fellows like Big Bill Broonzy, Blind John Davis, and a host of other bluesmen. I was the only white musician on these dates. Hugues Panassie, the (distinguished) French author of the jazz book, Le Jazz Hot, came out with a discography which included me as ‘the great Negro blues guitar player from Chicago.’ I did all kinds of recording dates.”

George Barnes would move on from blues in the late 1930s, to pioneering country, rock-a-billy, rock ‘n’ roll and pop/rock guitar, before becoming world-famous as one of the finest jazz guitarists of all time.

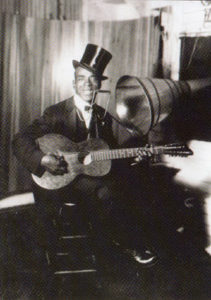

His mentor, guitarist Lonnie Johnson, must be regarded as one of the most influential, yet unsung, blues guitarists and singers of all time. Lonnie’s problem was that his guitar playing and singing were just too good. Lonnie made blues sound so polished and easy, he became overlooked and considered out-of-fashion by a particular coterie of white blues writers in the 1950s and 1960s. They didn’t consider Lonnie quite primitive enough.

Yet it was Lonnie Johnson who, as early as the 1920s, first laid down many of those guitar licks and vocal phrasings later copied by purveyors of what might be considered the more primitive-style of blues. Such bluesmen didn’t get their inspiration from the Mississippi Delta, they got it from Lonnie Johnson. Here’s Lonnie Johnson and Eddie Lang recorded in 1929.

So where did Lonnie Johnson get his inspiration from? Certainly, from his recording partner, the Italian-American jazz guitar virtuoso, Eddie Lang. Johnson and Lang were the first black and white musicians to record together, making innovative blues records during the 1920s. In the USA (but not in Europe) Lang was credited on disc as Blind Willie Dunn to disguise his being white, such was America’s segregation culture of the early twentieth century. Lang and Johnson were regarded, back in the 1920s, as the two most important jazz and blues guitarists in the world, not just in America. In my view, they still are. Apart from Eddie Lang, the only other guitarist known to impress Lonnie Johnson was Sylvester Weaver who, in 1923, was the first person ever recorded playing blues guitar, with ‘Guitar Blues’ and ‘Guitar Rag’.

Even earlier, two internationally-famous white guitarists recorded a Hawaiian guitar duet with some interesting blues-style slide note-picking in June 1917. The track was ‘Palakiko Blues’ and the guitarists were Palakiko Ferera, a Hawaiian of Portuguese descent, and his Seattle-born American wife, Helen Louise Greenus. The pair performed widely in vaudeville as Helen Louise and Frank Ferera and were the first big stars of Hawaiian music. While Helen unfortunately disappeared over the side of a ship sailing back to her home town of Seattle, in 1919, her husband went on to dominate Hawaiian music and sell millions of records around the world. Frank Ferera was the biggest selling guitarist of the era, influencing blues and Hawaiian guitarists alike. Here’s Helen Louis and Frank Ferera, recorded in March, 1917

Hawaiian slide guitar was introduced to America in 1893 when Hawaiian musicians demonstrated a technique, invented by Honolulu schoolboy almost a decade earlier, to hundreds of thousands of people visiting the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. The Hawaiian boy was Joseph Kekula, aged 11, and the most common estimate of his discovery is 1885. Around this time, Joseph experimentally slid a metal bolt he found, while walking along a railroad track near Honolulu, over the strings of his Portuguese guitar.

Also in Chicago in 1893, the Sears Roebuck Mail Order company opened its doors, selling and distributing such items as sewing machines, saddles and musical instruments, all over the United States. Improved road conditions, and the building of new railroad tracks, helped make this possible, and reduced the cost of obtaining guitars, harmonicas and horns considerably.

For affordability, size and ease of transportation, the smaller-bodied parlour guitar was often the purchase of choice, mainly because it was cheaper than the standard guitar, banjo or violin. Most early blues players, including Robert Johnson in the 1930s, preferred parlour guitars to standard concert guitars and banjos. But there was also another reason African-Americans were beginning to prefer the guitar over the banjo and violin. Wrote one of the world’s leading blues historians, Dr. David Evans:

“For blacks in particular the guitar lacked any residual associations with slavery, minstrel music and its demeaning stereotypes, or even with the South.”

Guitars soon became the instrument of choice for young African Americans, Dr. Evans suggests, because guitars were seen as neither rural nor traditional black instruments. Guitars carried an aura of urbanity and upward mobility: sophistication, if you like. As well as social reasons and its cheaper price, the guitar’s greater sound range also helped it usurp the banjo. You could emulate the chugging of a train and use a bottle or knife as a bottleneck or slide on a guitar. As the redoubtable folk music archivist, Alan Lomax, once noted, the guitar was capable of sounding like several parts at one, saying:

“The lone bluesman could pocket the fee for a whole orchestra.”

American Blues historian, David K. Bradford, quotes Charles Haffer, the nineteenth century African-American ballad singer, songwriter and street evangelist. Haffer associated the emergence of blues during the 1890s with the guitar’s new-found popularity among black musicians. Born in the 1870s, Mississippi-born Haffer said:

“I used to sing all the old jump-up songs. The blues weren’t in style then. We called them reels. The first blues I remember originated from a sheriff named Joe Turner. He was a kind-a bad man and if he goes after you, he’d bring you. His blues was very famous.”

So, what got these young black musicians interested in the guitar in the first place? One catalyst was the sensational success, starting in the 1878, of large groups of youths and Spanish students, known as estudiantinas, specialising in outdoor guitar serenades. These took Paris and other European cities by storm, setting the stage for the popularity of the Spanish guitar, giving rise to mandolin and guitar orchestras throughout Europe and the Americas and started the phenomenal Banjo, Mandolin and Guitar (BMG) movement. BMG groups even became nineteenth century equivalent of dating sites – a place where unmarried men and women could socialise. More importantly, the BMG movement led to the development of new industries to meet increased demand for plucked instruments, especially in the USA.

In the 1880s, steel guitar strings were introduced to help acoustic guitars compete with the brighter-sounding mandolin, then at the height of fashion. In the 1890s, guitar manufacturers started building stronger instruments to withstand the stresses of these high-tension steel strings. Stronger guitars and steel strings also allowed solo guitarists to start experimenting with bending strings and sustaining notes.

I only know of four black guitarists plying their trade in the 1890s – the four forefathers of the blues & rock guitar hero. Two, Charlie Galloway and Jefferson Mumford, were known to have been playing on the streets of New Orleans in 1885. By the 1890s, they were each leading string bands in New Orleans, both playing hot ragtime, the direct forerunner to the first recorded style of blues in 1914, the New Orleans sound later known as jazz.

‘Sweet Lovin’ Charlie Galloway even hired the legendary cornet player Buddy Bolden, who later took over his band. Buddy Bolden later employed Jefferson ‘Brock’ Mumford as a guitarist for the Buddy Bolden band, as it became known. Probably playing the guitar at the same time as Galloway and Mumford was the bluesman we know as Daddy Stovepipe. Born Johnny Watson in 1867 in Mobile, Alabama, we know Stovepipe played in a mariachi band in Mexico in the late 1890s. Obviously supremely versatile, Daddy Stovepipe would certainly be the earliest blues performer ever known, if only we knew the exact genre of music he was playing in America before his Mexican sojourn. Unfortunately, we don’t know what Stovepipe was playing, just as we don’t know what style of music Jefferson Mumford and Charlie Galloway were performing in the 1880s. As well as Daddy Stovepipe, Johnnie Watson also recorded under the names of Jimmy Watson, Sunny Jim and the Reverend Alfred Pitts. He cut his first record, ‘Sundown Blues’, in Richmond, Indiana, in early 1924 aged 57. It is thought to be the third-ever country blues captured on record. Amazingly, Johnny ‘Daddy Stovepipe’ Watson’s last record was made in 1960, at the grand old age of 93. He died three years later aged 96. His nickname was due to the stovepipe hat that he always wore.

The fourth African-American guitarist I know was playing in the 1890s was a Delta Blues guitarist by the name of Henry Sloan. Henry, who spent his life in rural Mississippi, is probably the earliest guitar player known in the history of Delta Blues. Born in 1870, Henry Sloan went on, says Dr. Evans, to tutor Charlie Patton, considered by many to be the Father of Delta Blues. This was in the late nineteenth century or very early twentieth century when both lived in Hinds County, Mississippi. Charlie Patton, today, of course, is universally known as the Father of Delta Blues.

It was during the 1890s, suggests Dr. Evans, that Henry Sloan became the first musician to set field hollers to guitar accompaniment. This was a critical step in the creation of modern blues.