UPDATED 8 OCTOBER 2016.

“A good read, my friend!”

Jason Vivone @ JVivone, Kansas City, 23 October 2014.

I’m currently researching mid-19th century San Francisco, working on a project that has nothing to do with historic blues or rock. However, wherever I look in life, I always hope to find something relating to early blues or popular music. And when I do, no matter how obscure, I like to put it on record, in posts like this for example.

|

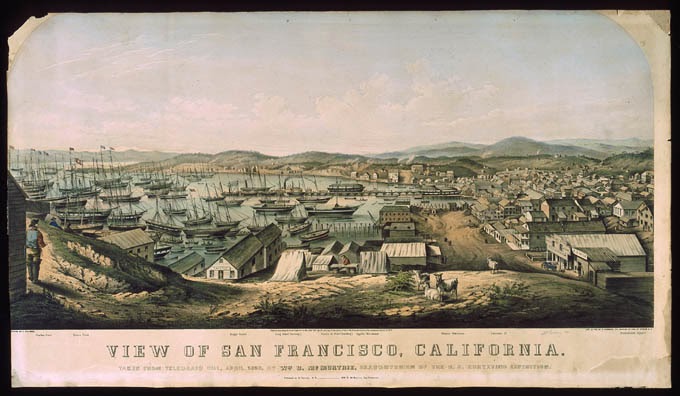

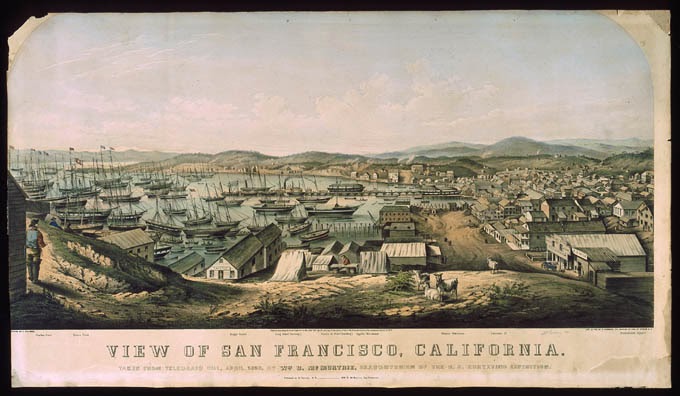

| San Francisco in 1849. Entertainment laid on in the city’s gambling casinos included a Negro chorus and one-man-band |

In San Francisco’s case, there are a couple of pre-blues-related landmarks I’d like to share. I rediscovered them reading (again) Herbert Asbury’s 1933 classic, “The Barbary Coast: An informal history of the San Francisco Underworld”. Asbury’s “Gangs of New York”, incidentally, was the 1929 book upon which director Martin Scorsese based his blockbuster 2002 film of the same name so, as a journalist and historian, the guy has credibility. Indeed, I think Asbury’s prohibition-era book even got a nomination for best original screenplay for “Gangs of New York” for one of 2002’s top U.S. movie awards.

I’ve had these facts in the back of my mind for years now, but re-reading Asbury and rediscovering they come from him gives them provenance. Over 80 years ago, Herbert Asbury described, in print, the musical entertainment laid on for the punters in San Francisco’s gold rush gaming houses.The Aguila de Oro casino, he said, featured a Negro chorus during August 1849, an event which, he said, introduced African-American spirituals into California. This was long before the boom in spirituals following the American Civil War due to the liberation of the South’s slaves: over 20 years before such famous pioneering African-American spiritual groups as the Jubilee Singers formed at Fisk University in 1871.

Another San Francisco gaming house in 1850, the Verandah, wrote Asbury, “presented a marvel who might well be called the daddy of the modern jazz trap-drummer”. Herbert’s not talking rock or 1950s modern-jazz here, of course, nor even 1940s be-bop. Since Herbert was writing in the early 1930s, Herbert’s talking jazz drummers of the 1930s, guys like Chick Webb and Gene Krupa. To give a point of reference, one seminal jazz song released when Herbert wrote his book was, “It Don’t Mean A Thing (If It Ain’t Got The Swing”), by Duke Ellington.

The anonymous entertainer whom Herbert described drumming in gold rush San Francisco, “wore pipes tied to his chin, a drum strapped to his back, drumsticks fastened to his elbows, and cymbals attached to his wrists.” All of these instruments he played in unison at the same time, making him one of the first one-man bands we know of.

“Moreover, he patted his feet which were encased in enormous hard-soled shoes, and with them made a tremendous clatter on the floor.”

This was in 1850, remember, and it wasn’t until some 40 years later that trap drum-sets, the forerunners to modern drum-kits, were introduced. As I explain in America’s Gift, only after trap drum kits were invented in the 1890s, could adventurous ragtime drummers begin experimenting with standing bass drums and foot-pedals. Such innovations freed up their hands, allowing them to bring in other drum kit components like cymbals, snare drums and tom toms.

|

| The New Orleans drumming and ragtime pioneer, Papa Jack Laine, photograph around the turn of the twentieth century |

Trap drum-sets introduced in the 1890s helped drummers consolidate and intensify their drum rhythms, setting the pace for the rest of the band. One of the best-known drummers of the 1890s was the white New Orleans drummer, Papa Jack Laine.

But Jack Laine wasn’t simply a drummer. From an early age, he arranged music for his various bands which he organised for such New Orleans events as dances, brass band parades and advertising extravaganzas. Indeed, it’s been reported Jack Laine was leading a band, aged 12, in “a ragged time” as early as 1885, long before ragtime was first demonstrated at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

Papa Jack Laine’s various Reliance Brass Bands featured musicians of all colours and races, even though this was against New Orleans’ newly introduced local by-laws, such was the bigotry of the times. Laine would say his lighter-skinned African Americans were Mexican or Cuban musicians. Many of these musicians went on to pioneer gut-bucket blues – one of the earliest blues forms we know of – and, later, the jazz that evolved out of this between 1900 and the 1920s.

However, back to San Francisco. Another interesting pre-blues historical snippet about San Francisco, according to the Los Angeles Times of 28 July 1928, is that the honky tonk drinking establishment originated in San Francisco. Under the headline “Honky Tonk Origin Told”, the Times wrote, “Do you know what a honky tonk is? Seafaring men of a few years ago knew very well, as the honky-tonks of San Francisco’s Barbary Coast constituted perhaps the most vivid spots in their generally uneventful lives.

“The name originated on the Barbary Coast and was applied to the low ‘dives’ which formed so great a part of this notorious district. In these establishments, which were often of enormous size, much liquor was dispensed at the tables which crowded the floor, and entertainment of doubtful quality (we’ll come to that later) was given on a stage at one end of the room.

The honky tonk, as a matter of fact, was the predecessor of the present-day cabaret or night club, the principal differences being that the prices were lower and that the former establishment made no pretence of class.”

Something else you might find interesting about San Francisco’s famous Barbary Coast is that it used to be known as Sydney Town during the gold rush days. This is because some 10,000 mainly English criminals – escaped and former convicts from Australia – established and ran the criminal underworld there, running brothels, grog shops, gambling dens and X-rated sex shows, often between humans and animals. Because most had sailed to San Francisco from Sydney, Australia, these hoodlums were known as the Sydney Ducks.

Wrote a San Francisco newspaper of the era, “The upper part of Pacific Street, after dark, is crowded by thieves, gamblers, low women, drunken sailors, and similar characters … Unsuspecting sailors and miners are entrapped by the dexterous thieves and swindlers that are always on the lookout, into these dens, where they are filled with liquor – drugged if necessary, until insensibility coming upon them, they fall an easy victim to their tempters …

|

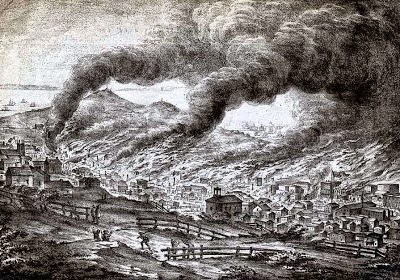

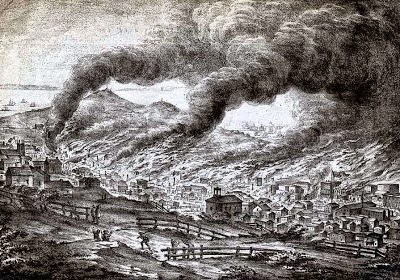

The Sydney Ducks first torched San Francisco on Christmas Eve 1849,

destroying 80 buildings as this contemporary scene depicts.

Enterprising capitalists were selling buckets of water for a dollar each. |

“When the habitués of this quarter have a reason to believe a man has money, they will follow him for days, and employ every device to get him into their clutches … These dance-groggeries are outrageous nuisances and nurseries of crime.”

The Sydney Ducks even burnt down huge swathes of San Francisco an unbelievable six times, between 1849 and 1851. This was usually in retribution towards those businesses who had refused to pay them protection money. The Ducks would also use the fires to distract San Francisco’s law-abiding citizens from their pillaging and murdering

Taking a lead from Australian aborigines, who regularly set light to the bush, the Sydney Ducks always waited for south westerly winds so that their own area of Sydney Town would escape the fires.

The citizens of San Francisco eventually became so enraged that, in 1851, they took the law into their own hands, forming a Vigilance Committee, the largest and most organized vigilante group in America’s history. Two Sydney Ducks, Samuel Whittaker and Robert McKenzie, were illegally hanged for arson, robbery, and burglary. The remaining Sydney Ducks fled San Francisco and just two weeks after the hangings, Sydney Town had only a few dance halls, saloons, and brothels remaining. That relative peace would only last for two years, however, before criminals started to once again return to Sydney Town. The area wouldn’t become known as the Barbary Coast until the 1860s.

It’s all fascinating stuff and you’ll find much of this in Herbert Asbury’s “The Barbary Coast: An informal history of the San Francisco Underworld”.

And if you want the history of the blues, you’ll find it in America’s Gift. Both books are available on Amazon.